Lyndon Township author Craig Toepfer looks back, sees transportation's alt-energy future

When Craig Toepfer was a Ford Scholarship student in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan, he found himself more interested in windmills than cars. One summer he toured South Dakota with a pickup, buying a couple of 1930s-vintage wind turbines with high-speed, aero-style rotors.

Windmills and cars have never been far apart throughout Toepfer’s career.

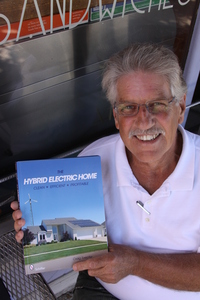

Craig Toepfer's book on home energy production came out in January. He sees the potential of powering electric cars through this means.

Ronald Ahrens | For AnnArbor.com

Now, as the author of “The Hybrid Electric Home: Clean, Efficient, Profitable,” published in January, the Lyndon Township resident has shown how to bring windmills, solar panels, and cars together.

“I’m waiting for my first royalty check,” he says playfully.

His blue-gray eyes gleam and the corners of his mouth turn up under his mustache as he tells of his long discipleship to such visionaries as Buckminster Fuller, who was preoccupied with concerns about sustainability, and Marcellus Jacobs, a pioneer in wind energy.

After graduating from the U-M in 1972, Toepfer worked in engineering for Ford Motor Co. Meanwhile, he dabbled in alternative energy, putting up a wind turbine in Scio Township that he says was one of the first in the country to be connected to the power grid, sending out surplus current. He placed another in western Washtenaw County in 1980.

During the 1980s he took a job with Jacobs Wind Electric Co., near Minneapolis, and oversaw the construction of wind turbines, even placing one on the Golden Gate Bridge to provide power to the administration building on the San Francisco shore.

In these years he collected documents and historic photos related to what Jacobs himself called “the wind business.” And Toepfer amassed a collection of wind turbines that at one point totaled around 100 items.

The generating plants manufactured by Delco starting in 1916, and by dozens of other companies, were another focal point in his collecting. “They were selling the hell out of them, they were going crazy,” he says. Delco's kerosene-powered generators let farms and rural businesses create and store their own electricity long before the Rural Electrification Act of 1936 — which Toepfer reviles — stretched power lines across the landscape.

His return to Ford coincided with the renewal of interest in electric vehicles (EVs). He became secretary for an important international committee that established technical standards for EVs, and represented the Society of Automotive Engineers on the National Electrical Code panel.

He also served as an auto industry representative with the Electric Power Research Institute’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Working Council.

“In all of these capacities I participated in developing standards for connecting EVs and plug-in (hybrid) EVs.”

After retiring from Ford in 2001, he resumed consulting on projects he finds engaging, like the recently finished wind-and-solar, hybrid-electric plant on an organic farm in Hillsdale County.

Poring over flow charts, he muses on questions of ultimate energy efficiency. He says the relative efficiency of vehicles with internal combustion engines and battery-powered EVs isn’t so different because, either way, most of the energy created is lost.

“Electric vehicles are nice, but it’s pretty much a net wash from an energy standpoint — unless we can increase the amount of solar, wind, and hydro energy that goes into the mix.

“If we can power our cars off the wind and the sun, then we get rid of the 80-percent losses in the transportation industry that are tailpipe gasses.”

He believes that consumers creating their own energy through the use of wind turbines, solar panels and — when possible — hydro-power, and storing the surplus current in batteries, can turn the equation around.

“Without that, our transportation system and our energy system are going to kill us,” he says, referring to climate change stemming from the emission of greenhouse gasses. “I mean, I hate to be so brutal about it.”

He says, “This is where the electric vehicle really comes into play.”

According to WikiAnswers, the average driver travels 33.4 miles per day. When it goes on sale late this year, the Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid is designed to travel at least 40 miles on rechargeable electric power alone.

The tipping point, Toepfer believes, will come when federal energy subsidies become unsustainable and the recovery costs of increasingly obscure supplies become prohibitively high.

Comments

Epengar

Fri, Aug 20, 2010 : 12:04 p.m.

It's amazing how influential subsidies can be. We could make huge improvements in the health of our citizens and our environment if we reduced the gov't subsidies for fossil fuel production, corn, and cotton and spent that money on organic agriculture and cleaner energy generation.

runbum03

Fri, Aug 20, 2010 : 7:41 a.m.

A great article, because it takes the emotion and politics out of AE. Engineering facts never change. A lot of folks don't realize we once had electric cars, so we've been there and already done that. Our current efforts (pun intended) are so retro.