Ann Arbor Symphony closing out season with Mahler's massive 'Tragic' Symphony

How to end a season? For the Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra in recent years, the answer has been a grand work—2012’s "Carmina Burana," for example.

This year is no exception. Saturday at the Michigan Theater, the orchestra, under the baton of Music Director Arie Lipsky, closes out its 2012-2013 season with one massive, towering work: Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 in A Minor, often called “the Tragic.”

There are many questions about whether that title was one Mahler bestowed on the work, or wanted attached to it. But it’s a detail, among many, about this work, that continues to resonate as the work passes its 100th birthday.

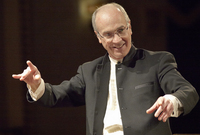

Arie Lipsky

Preparing this 80-minute, four-movement symphony that Mahler premiered in 1906—music that Lipsky calls “out of this world” and “a big project”—has required Lipsky to confront all these issues, and more.

Mahler, Lipsky noted, wrote the symphony at what seemed to be a happy time in his life. And indeed, the work has moments, and movements, of great loveliness.

“He wrote it around 1904, and he was almost freshly married to Alma, and around that time his second daughter was born and everything was going very well in his career,” Lipsky said.

“At the same time, according to Alma, he foresaw at that time some dark clouds,” Lipsky continued. Those clouds—very Mahlerian premonitions (according to Alma: his forced firing from his post at the Vienna opera; the death of his first daughter Maria Anna; and the heart ailment that would eventually take his life)—take form in a “fate motif” that permeates the symphony; in an ending that removes all light from the fate motif; and especially in three hammer blows, struck in the percussion section, woven into the finale.

“That’s why the blows appear in the last movement,” Lipsky said. Alma said her husband described them thus: ‘’It is the hero, on whom falls three blows of fate, last of which fells him as a tree is felled.’’

But even the number of blows, or who, exactly, plays them and how, is unclear. Mahler wrote five, originally, Lipsky said. And then, there were three, and also two—the third replaced simply by ominous expectation of a blow that does not materialize.

“We are going to have two hammer blows,” Lipsky said. “It seems to me the more I study his music, there’s a place that everybody kind of waiting, he built this expectation, but he just shied away and was a little superstitious—as if he was reluctant to hit himself.

Then there is the challenge of making the blows heard. “He wanted it to sound hollow and dull,” like an axe, Lipsky said. “But he builds this fantastic climax, and it’s difficult to hear it above the orchestra.”

And who will play these?

“One of the percussionists plays the blows,” Lipsky said. “I’m going to initiate a conversation with John Dorsey, our principal percussionist, to see what solution he has. It should sound a little metallic, but not with a thump. And we will talk about his placement in the orchestra, where he plays it. There is a visual element which is important.”

PREVIEW

Mahler Symphony No. 6

- Who: The Ann Arbor Symphony Orchestra. Arie Lipsky, music director and conductor.

- What: Mahler Symphony No. 6 in A Minor.

- Where: Michigan Theater, 603 E. Liberty St.

- When: Saturday, 8 p.m., with pre-concert lecture at 7 p.m. for ticket holders.

- How much: $10-$58, online at a2so.com and by phone at 734-994-4801. Discounts for students, seniors and groups.

“It’s almost half and half which way conductors do it,” Lipsky said, based on recordings.

But though Lipsky, as an orchestral cellist, has played it with the scherzo first, “I always felt it was too much, these two energy-packed movements side by side,” he said.

So he will conduct the work with the scherzo in third place. The andante, which, as he pointed out “does not include the fate elements” and is filled with “Mahleresque colors, beautiful themes and harmonies that take you to a completely different place,” will come second.

“I believe you need to separate the first and third movement (scherzo), which are a little similar in their energy and almost aggressive mood.”

Though Lipsky has played the Mahler numerous times, Saturday marks his first performance of the symphony as a conductor. “It’s something to really look forward to,” he said.

First time or not, he will conduct, as usual, by memory.

It’s not necessarily harder to conduct Mahler without a score than any other composer, he said. But Lipsky acknowledges the difficulty of communicating some of Mahler’s instructions—“increasingly complicated as he aged and conducted more”—to the musicians. For example, he said, Mahler may write a passage as piano (soft) for the violins and double forte (very loud) for the woodwinds, and change it around in the middle.

“He wants the melody to change colors in the middle, so the intensity of the melody continues but comes from different place in the orchestra, with a different color.

“The intensity of the music changes place and colors, and this is one of the most challenging things to show when you’re conducting. It rarely appears in other composers.”