A historical look at schizophrenia raises questions still relevant today

As in any good discussion, connections were made on concrete, individual levels — this was not a history lesson or discussion of abstract ethical issues specific to one group of people but rather a dialogue of attitudes and health issues that still pervade our entire culture today.

In one way, the conversation was circular in that it began with a reflection of current events and ended with questions from the audience who referenced concerns in their current lives. For example, one woman used to be a nurse working with the mentally ill, and she is dismayed at the lack of care many now receive due to practical elements such as space and money. Gone are the days of institutionalizing individuals for weeks, months or indefinitely; now they are released within days (or less). This is not a reflection on the efforts of individuals working with the mentally ill, but rather of how a larger system is failing people.

Separately, Metzl opened his talk with commentary on current events — primarily the recent shooting in Arizona — and how mental illness is addressed in the news in relation to violence.

But the in between was a fascinating, and disturbing, history of how the definition of schizophrenia changed over time — including to whom it was attributed and how this was an enactment of larger social forces playing out. Furthermore, one of Metzl's goals is to show how particular attitudes and assumptions about schizophrenia are remnants of an ongoing conversation about race in America.

Between the 1930s through the 1970s, notions affiliated with schizophrenia shifted in vital ways. The term schizophrenia was invented at the turn of the century, and, in the early decades of the 20th century, it was assumed to be associated with genius and shyness — not violence. And later it was more frequently associated with middle-class white women whose crimes included shoplifting and embarrassing their spouses in public; advertisements in Ladies Home Journal and similar magazines were found. In the film The Snake Pit, Olivia de Havilland suffers from it. So, what happened?

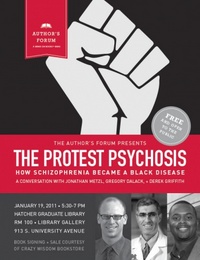

From the late 1950s onward, schizophrenia became a metaphor for race. As Metzl points out, a "racial schizophrenia" maps onto the discourse of a racially split country. Black activism created a public anxiety and one effect was how this was shaped in psychiatric discourse — including a change in the definition of schizophrenia. One tool psychiatrists use when treating patients is a reference book entitled Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) which is periodically updated. By 1968 the definition now attributed qualities of hostility, aggressiveness, and ascribing to others what the patient cannot accept in him/herself. In addition, advertisements in psychiatric journals for anti-psychotic drugs no longer depicted housewives, but African-American men. One example of an ad for Haldol from the 1960s showed an angry black man with a fist and the caption, "Assaultive and belligerent?"

So, imagery and language associated with the illness had changed — and with that — the individuals who were diagnosed with this disease also changes. In his book, Metzl then uses the Ionia State Hospital for the Criminally Insane as an example of this shift. A hospital which had primarily housed white women as patients housed an increasing number of African-American men in the 1960s and 1970s. The Michigan hospital closed in the early 1970s and soon re-opened as a prison.

Connected with this are questions that still need to be addressed including stigma against mental illness (and schizophrenia in particular), racial stigma, the intersection of these, and how each of us carries these — unconsciously or not — in our daily lives. These attitudes play out in decisions we make in our personal sphere and in how we shape our larger world.

As mentioned above, there was a panel discussion which also addressed such issues as how doctors can be aware of what cultural biases were incorporated into their training, what constitutes care, how an awareness of culture helps see the meanings patients ascribe to certain words and ideas, how difficult it is to talk about race and an awareness of structures and patterns at play in individuals lives, among other things. This book and discussion show how one small slice of events in society can mirror so much more.

An interview with Metzl about the book can be found on Beacon Broadside website here.

This event was presented by the Author's Forum: a collaboration between the University Library, U-M Institute for the Humanities, Great Lakes Literary Arts Center, and the Ann Arbor Book Festival. Additional sponsorship for this event provided by the Department of Women's Studies and of Afroamerican & African Studies; the Program of Culture, Health, and Medicine; and the Centers on Men's Health Disparities and for Research on Ethnicity, Culture, and Health. Books were available for signing courtesy of Crazy Wisdom Bookstore.

Julia Eussen received her B.A. in English from Kansas State University. She is currently a graduate student in Eastern Michigan University's Professional Writing Program. She is also an active member of the Ann Arbor Classics Book Group and has recently begun to re-acquaint herself with good poetry. She can be reached at jeussen at emich dot edu.

Comments

REBBAPRAGADA

Tue, Jan 25, 2011 : 8:26 p.m.

We need to recognize the difference between eccentric behavior and mental illness. The schizophrenic person cannot rationally understand the fact of his or her illness and the need of treatment. To defend mental well-being, the health care services should be provided to all free of cost. This illness recognizes no racial, gender, or socioeconomic status of the man.

katie

Tue, Jan 25, 2011 : 2:11 a.m.

I've never thought of schizophrenia in terms of a person being black. All of the people I've known with it were white, and those in the news seem to be white, like the Unibomber and the recent AZ shooter. I do not doubt that there may be racism involved in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia, but the article did not make it clear how that manifests. Is there a stereotype? Are blacks with schizophrenia jailed rather than treated? It seemed a little vague in the story.

Julia Eussen

Tue, Jan 25, 2011 : 3:29 a.m.

My apologies for the vagueness! I did not mean to imply that African-Americans are jailed rather than treated. There is, however, a history where the definition of the disease changed greatly - and with that to whom it was attributed. Perhaps the best reference I could give you is this online interview with Dr. Metzl on The Root: <a href="http://www.theroot.com/views/schizophrenia-political-weapon?page=0,0" rel='nofollow'>http://www.theroot.com/views/schizophrenia-political-weapon?page=0,0</a> Among other things, in it they point out that African-American men are diagnosed with schizophrenia at a rate 4-5x greater than other groups. Dr. Metzl offers a couple of possible explanations as to why.

stunhsif

Mon, Jan 24, 2011 : 4:51 a.m.

My mother's younger brother was diagnosed at the age of 21 while at the Univ of Indiana. He is now 66 years old. He did graduate with a degree in Mathmatics with a 3.9 GPA. His first sign was hearing voices that told him to do things and tormented him. He underwent shock therapy which helped and drug therapy. While under drug therapy he was able to hold menial jobs though, after college he lived at home with his mother and father until they died. Over the years at living at home he fought with his parents over taking his drugs and often times would not take them. He then spent years at a time, locked upstairs in his room. After his mother ( my Grandpa and Grandma ) and father died he moved into a halfway house where he still lives. His SS disability insurance is his only income. What a waste of a life, he was a genius, I am certain. If he had stayed on his medication he could have lived a much more normal life.

Julia Eussen

Tue, Jan 25, 2011 : 3:14 a.m.

Thank you so much for sharing this - it is sad and it is a reminder that a person is not just an illness, but a multi-faceted being with potential.