U-M Press introduces us to 'Ladies of the Lights: Michigan Women in the U.S. Lighthouse Service'

An article in Michigan History magazine first brought Patricia Majher's attention to the subject. Kathy Mason's 2003 cover story, “Mystery at Sand Point Lighthouse,” described the suspicious circumstances surrounding a fire at this Escanaba lighthouse that claimed the life of keeper Mary Terry, who had been given the job after her husband's death from tuberculosis.

Almost as interesting as the story, says Majher, “was this table of 50 other women who had served as lighthouse keepers in Michigan. And I had no idea one had served, let alone 50!”

The thought stayed with her, tucked into the back of her mind, until she landed a job at the Michigan Women's Historical Center and Hall of Fame in 2007. As assistant director/curator, she was put immediately to work designing an exhibit for the museum's changing gallery, and an opportunity to delve the questions Mason's article had raised was born. The exhibit was “hugely popular” at the historical center, notes Majher, and is now a traveling exhibit available to schools, museums and libraries. “When it was sent on the road, I thought I'd done enough research for a book, so I wondered if anyone was interested. And the University of Michigan Press was.”

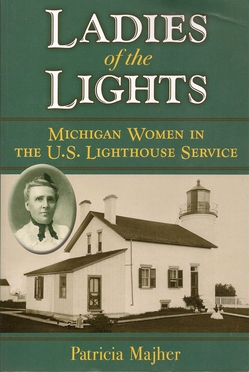

The result is “Ladies of the Lights: Michigan Women in the U.S. Lighthouse Service” (University of Michigan Press), a slim volume collecting just about all that is known about the women who kept Michigan's Great Lakes vessels safe from harm between 1849 and 1954.

Its museum-exhibit roots shine through in the book's organization, which begins with a brief history of women in the National Lighthouse Service (a federal job), explains why Michigan has the most female keepers of anywhere in the nation (because we have the most lighthouses by far), and brings us up to speed on the typical duties of a lighthouse keeper. We learn that most women got the job through a male connection and that, horribly, this connection was most often a husband who died in the service.

A chapter each is devoted answering questions such as “What special hardships did women face?” “Were any lighthouse keepers also mothers?” and “What were the contributions of wives of male keepers?” We are introduced to some of the most interesting and longest-serving women in “Sixteen Who Served,” and an interview with Michigan's last female lighthouse keeper, Frances Wuori Johnson Marshall, is an exquisite treat that absolutely merits the “saved the best for last” position in the book. AnnArbor.com chatted with Mahjer, who now edits Michigan History Magazine, about research, discrimination, and awe-inspiring hard work.

Were there challenges in translating the exhibit to book form?

I needed a whole lot more photographs. That was a problem, because although the male lighthouse keepers all had their portraits done by the Lighthouse Service, they didn't do that for the women. So all the pictures we have of female keepers are family photographs. Now that the book is out, there's the hope that the family members of these women will come forward with more photographs. And there's a lot more writing involved in a book than in an exhibit, so I ended up doing another six months' worth of research.

Wait, what was that about men and photographs?

Women were treated a little differently in the service: no uniforms, no formal portrait that the service would have paid for. It represents a conflict that there was with women serving in that part of the government. They were paid the same as men, though.

I thought that was pretty interesting, that female lighthouse keepers were paid the same as men, given that equal pay in general is something that we're still struggling with today and that the Lighthouse Service didn't seem to mind discriminating in some ways. Do you have any thoughts on how it might have worked out that way?

I do not. It started in the 1830s, (and the service seems to have) said, “Well, the women who survived male keepers who had died on the job had done that job, and they were there,” and it was an opportunity to help them out as widows and sometimes mothers. It was almost giving them a job as a reward or a social service, much in the same way as men were assigned the lighthouse jobs for serving in the Civil War. So there was this paternalistic opportunity to help people.

Do you have a particular personal connection with lighthouses or boat and lake culture?

(Laughs.) No, my interest was more from the standpoint of women's history. Sometimes when I give presentations, people ask technical questions about, say, what color the range lights were, and I'm not so well-versed in that.

Tell me about the research you did — where did you find all this information? Did you spend much time in libraries, “in the field”?

A combination. There are libraries in certain communities along the coast of Michigan which have repositories of information on the lighthouses in their areas. The Bacon Memorial Library in Wyandotte, for example: There were a number of lighthouses along the river and that library maintains a good file of keepers, and there were a couple of women. So I was either traveling to the library or communicating with the librarian by phone. For basic information about who served when, Thomas and Phyllis Tag maintained a history of the Great Lakes, which is great so you don't have to go to the national archives.

Do any mysteries remain for you that you wish you'd been able to find out more about?

It's unfortunate, but many of these women's stories have been lost. And there was — you know, we don't have much knowledge of the women after they left the service. (Sometimes they) married again and that may have changed their name, so it was very difficult to trace the women afterward. I thought that was very unfortunate, because I would have loved to know that. Again, I hope that descendants come forward with post-service stories that we can gather and fill out our knowledge of these women.

I loved reading the interview with Frances Wuori Johnson Marshall. She jumps off the page like an absolute hoot. What was she like in person?

She was just really feisty and funny, and I actually had the pleasure of driving to her home and interviewing her there. She's a little frail in her late 80s, but she still lives alone and she's still sharp and enthusiastic. She didn't really want to leave (the lighthouse), but she was newly divorced and had a new baby and was struggling to maintain things on her own. [Note: This is an awfully nice way of putting it. The interview in the book reads like this: Q. And (your daughter) was only a year old or so when you all moved? A. Eleven days. Q. Why did you leave at that point? A. Her father left and I couldn't keep up the furnace and all that. So my dad came and got me. Ouch!) But she would have stayed. She still lives in the area and spends time out there, and I know she goes to programs (focused on the lighthouse) and is very much in touch with the museums and society.

Do you have a favorite of these stories or one lighthouse keeper whose story you feel particularly drawn to?

Well, of course, Francis because I met her. And Caroline Litogot — she later married — has a famous connection because she's one of Henry Ford's aunts. She's one that married a disabled Civil War veteran and he was named the keeper, and then he died and she continued on. She had to fight for her job. The community wanted her to keep her job and even appealed to the senator — Zachariah Chandler was Michigan's senator at the time — and so she stayed on, but the lighthouse inspector didn't think she should for some reason.

So I just think that's very inspirational, that the community rallied around her and a U.S. senator pleaded her case in Washington. She got married again and stayed on the island and started a second family; about a year after her second child was born, she left. There are some good pictures of her. You can see that early on she's all rosy and plump-cheeked, and by the end of her service she was pretty gaunt. It was hard work, and you didn't stay rosy and plump-cheeked for long. It did take a toll on the women, and they aged quickly. There are some wonderful photos of her at the Henry Ford. She one that we have more information on.

Is there anything else we should know?

A lot of these women who were mothers of large families; you kind of have to tip your hat to them. The first had eight children and her husband drowned and she soldiered on, keeping the light and raising the children in the wilderness. Another one had 10 children. These women were balancing families and physically demanding jobs with great responsibility.

Each woman is so distinct. I think there are, in the lighthouse business, families of lighthouse keepers where more than one person in the family worked in the service. And not just couples. The most well-known families all had women: the Sheridans on Lake Michigan and the Corgans on Lake Superior (each had keeper women who bore a keeper son) and the Garritys on Lake Superior had a mother-daughter combination. So I think that was important.

They weren't just marginal figures at minor lights; in these prominent families — which all have Irish names, interestingly — they all had women who served a prominent role. These women were important and were highly respected. A lot of attention is paid to the woman on the cover, Elizabeth Whitney Williams, who was our longest serving woman at at 41 years. She's got books about her and was written into a play.

"Ladies of the Lights: Michigan Women in the U.S. Lighthouse Service" is available from the University of Michigan Press.

Leah DuMouchel is a freelance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Sarah Rigg

Tue, Dec 21, 2010 : 9:36 a.m.

Leah: I'm a total skeptic about the supernatural/paranormal in general, so no. I was there fairly late at night (9 p.m.) when it was dark and deserted, and I never felt a "presence" or anything.

Leah DuMouchel

Tue, Dec 21, 2010 : 9:33 a.m.

Sarah, I bet she'll like it - I had a great time reading it. And...WAS the lighthouse haunted? I would totally come back and do some spooking, wouldn't you??

Sarah Rigg

Tue, Dec 21, 2010 : 9:21 a.m.

Leah: I'm from Escanaba, and I used to work as a docent at the lighthouse there and got asked about whether it was haunted by the lightkeeper. I bought this book immediately upon reading your review to give to my mom as a Christmas gift since she's a lover of Michigan history!