"The Changing Environment of Northern Michigan" details studies of U-M Biological Station

Among the illustrious University of Michigan’s many long arms is its Biological Station, a small village on the southern tip of Douglas Lake, maybe 20 miles south of the Mackinac Bridge. It has all the necessities of academic life — varied sorts of housing, a big communal cafeteria, a lecture hall, a multitude of labs and a huge library — nestled on well over a thousand acres of northern Michigan landscape that’s busily studied, analyzed, classified and documented by students every spring and summer as they come up to spend a few weeks on the site earning field biology credits (and a few hardy faculty who live there year-round).

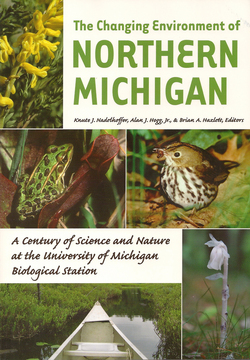

So to celebrate the station’s centennial, it only seems fitting that all that documentation gets put to use in a new book, “The Changing Environment of Northern Michigan” (University of Michigan Press).

It’s a dense tome, packed with information about the flora and fauna that call the top of our peninsula home. It begins by telling us the history of a parcel of land donated to the University by timber barons — who had presumably gotten every last scrap of saleable wood — for use as a civil engineering camp in 1908. The following April, the U-M Board of Regents heeded a plea from zoology and fish expert Jacob Reighard to participate in a newfangled branch of science called “ecology,” and set aside $2,000 for a research station on botany and zoology on the same site. Time was on the biologists’ side: by 1929, there was enough forest regrowth to interfere with the engineers’ survey lines, so they moved to a site near Jackson Hole, Wyoming. And the life scientists obligingly made use of their abandoned buildings.

Each chapter of the book was written by a contributor who has done or is still doing research at the station. The histories of the land, people and vegetation are followed by a long middle section in which you could find a fairly detailed analysis of pretty much any class of organism that interests you: fungi, mammals, birds, algae, vascular plants and lichen, to name a few. In each of these discussions, we see how specific types of organisms have changed over the last century, and the last few chapters are devoted to a more broad discussion of the agents and possible implications of that change. AnnArbor.com caught up with editor Alan Hogg to ask him about the book, the changes and what he’d like to see in the next hundred years.

Alan Hogg

U-M Press

Tell me about your role at the Biological Station and in writing the book. My role at the station was that I did my Ph.D research there. I was looking at the reaction between ozone and nitrogen oxide, the pollution on the forest, and how it’s helping or harming the trees. I lived up there for two full years, which was just fantastic. Now…in the summer I assist (local poet, teacher and writer) Keith Taylor with a course of Great Lakes literature and environmental writing. And of course I’m an editor for this book — putting it together and trying to create a theme and tone so it could be accessible to any interested Michigan resident.

How were the contributors selected? They all have a connection to the Biological Station and have done research there, so they’re the experts. In some cases, there was one clear person, and in others there were a few. We tried to get ones who were doing still research.

This is a pretty detailed book, full of technical information that was a definite mental workout for the layperson. How do you see it being used? As a textbook, maybe, or a field guide? To a certain extent, a field guide. There are some things we could include an exhaustive list for, but there are 7,000 kinds of algae and that would have taken up the whole book. So we had to balance the information with how much space we had — it would be more of a guide of how things have changed and why. We tried to make it not as academic as a lot of the first drafts were, and I think it was more successful in some cases than others.

The theme of this book and of every chapter is change. Has there been more change in northern Michigan than you would expect to find over a period of 100 years anywhere? I think of course there would be some change in pretty much anyplace, but northern Michigan, for a couple of reasons, has a more unique range of that change. (One reason involves) warming — any species that needs colder temperatures, the ones who can’t fly or get across the ice (at the tip of the Lower Peninsula), they’ve hit a wall. So it’s an interesting way of observing that. The other is because right before the biological station was started, the area had been logged and then burned. So the recovery from that was a change that I don’t know if you would see in other places. We were really starting from scratch, and it takes a long time for that.

The second half of the book deals pretty extensively with climate change and its possible results. What role, if any, do you see the research done at the Biological Station playing in setting the course for either regional or national responses to it? I think the real strength is that over the past 100 years, we’ve looked at and tried to understand how things have changed. If you’re going to predict how something might change in the future, you first have to understand how the machine works before you can say what’s going to happen next — before you can predict how a dropped ball is going to come down, you have to understand how gravity works. I think it’s also a good point to make that it’s not just climate change, but also land use and development changes, and invasive species. And too, it’s one place, but there are all kinds of field stations across the country and across the world, so we’re one spot within a bigger network. If you’re measuring the temperature across the globe, you have to use a lot of thermometers.

Do you see a different role for the scientists trained there? One of the things is not just the scientists, but the students. They discover an interest in insects, say, and go to graduate school to study them. Inspiring students to get interested in ecology of this region and ecology in general has an effect…(even) as they move on to other things in their lives and spread out across the world.

Does the Biological Station have plans to make any changes in anticipation of the warmer climate? Or will your role be more that of a careful observer? Certainly it will be an observer, but U-M itself has been making changes on all of its campuses, trying to green them and have a lower ecological impact. So the station will participate in those changes, although I don’t know all the specifics. My first year was in 2002, and on a simple level, I’ve seen the lightbulbs change like everyone else is doing. I guess we’re really trying to observe these changes, but part of the response has to be minimizing our impact in terms of carbon emissions.

Douglas Lake watersheds.

Courtesy U.S. Geological Survey

In the 200th anniversary edition of “The Changing Environment of Northern Michigan,” what would you hope to read? I’d certainly like to see a chapter about how humanity as a whole has responded to all of these changes. I’d like to say, “A hundred years ago, we saw a lot of things starting to happen, and here’s how we learned to fix things,” … I’d like it to find a larger audience and more people who are interested in backyard ecology or the ecology of their state, even to the point of documenting how cottages on lakes have changed their shorelines to protect them from erosion, or to see that some mammals have been moving north or south but figured out how to adapt. Hopefully, if the first hundred years was about how we got over logging and burning the land, the next hundred would be about how we got over altering the climate.

Is there anything else we should know? I would like to emphasize again that “change” is not just climate change, but also how we’re using the land — woods have become farms and farms have headed back toward forest, and that really changes things in term of species. And invasive species, too — we don’t have anything in there about Asian carp because that’s certainly a new thing, but we cover a lot of the other ones.

What do you think about the Asian carp, anyway? The Great Lakes are such amazing things that to threaten their ecosystem in some way to keep open a commercial canal is really a big tradeoff to me. If it were up to me, I’d just shut down the canal. … You see how the zebra mussels have really changed things, and that happened while we weren’t really paying attention. But we’re paying attention now, so don’t we have a responsibility to do something?

You can get a copy of "The Changing Environment of Northern Michigan" from U-M Press, Borders or Amazon.com.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Epengar

Tue, Jan 26, 2010 : 12:04 p.m.

Readers might like to know that in addition to hosting extensive research efforts and courses for university students, the Biological Station also offers week-long "mini-courses" to the general public. There are three this year: Birds of Northern Michigan, Forest and Landscape Ecology, Sustainable Urbanism: Urban Design with Nature. Tuition is not cheap, but the courses run all day for 5 days, and are taught by experts in the field. For instance, one of the bird course instructors is the former director of the DNR's Non-Game Wildlife Program, and one of the Forest Ecology teachers is Burt Barnes, Professor Emeritus of Natural Resources. http://www.lsa.umich.edu/umbs/courses/minicrses

aareader

Tue, Jan 26, 2010 : 11:22 a.m.

Great Article. Have been there. It is a great asset for the U