Bridge column, March 20: Don't tell opponent how to succeed

At the bridge table, some bids paint a perfect picture of a player's hand. But if an opponent then becomes the declarer, he has been given a road map for playing the contract.

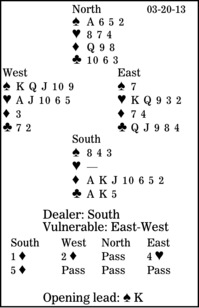

In this deal, South was in five diamonds. What did he do after West led the spade king: ace, seven, four?

West's two-diamond overcall was a Michaels Cue-Bid, promising at least 5-5 in the majors. After East jumped to four hearts, South, unsure who could make what, sensibly rebid five diamonds. Then East, eying the vulnerability, passed. (Five hearts doubled should go down two, minus 500.)

South had three losers (two spades and one club) and only 10 winners (one spade, seven diamonds and two clubs). But he had a huge advantage, knowing that East had started with a singleton spade and could not reach his partner's hand.

At trick two, declarer started a partial elimination and endplay by ruffing a heart in his hand. He returned to dummy with a trump to the eight, ruffed a heart high, played a diamond to the nine, and ruffed the last heart. Then South cashed his top clubs and played a third club.

East won but had no answer. Whether he led a heart or a club, South would sluff a spade loser from his hand and ruff on the board. Declarer would take one spade, eight diamonds and two clubs.

I am not saying West's two-diamond overcall was wrong, but be aware of the risk.

** ** **

COPYRIGHT: 2013, UNITED FEATURE SYNDICATE

DISTRIBUTED BY UNIVERSAL UCLICK FOR UFS