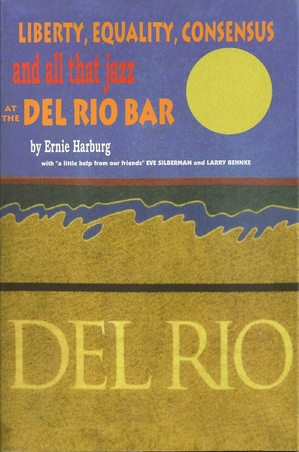

Del Rio's "Liberty, Equality, Consensus and All That Jazz" recalled in book

Whether that end represents a tragic failure or an astonishing success — well, that’s a matter for the other 154 pages.

Even those of us with years of Detburgers and wheat-crusted pizzas quite literally under our belts may not know that the Del began as Harburg’s side project to bring in backup income when he decided not to pursue tenure as a University of Michigan social science researcher. Instead, he joined forces in 1969 with his wife, Torrey, and a data programmer with a passion for jazz named Rick Burgess to buy a bar in a then-rough-and-tumble neighborhood where knifings, independent hookers and the flashing red lights of cop cars were common enough to be unremarkable.

Their makeover of the place (on the corner of Washington and Ashley, now the Grizzly Peak's Den) started with a community barn-raising of sorts to introduce the proper dark ambiance and liberate the beautiful vintage tin from a yellowed drop-ceiling, but it didn’t stop with cosmetics. There was also the fun of telling burly men dressed in black that the new owners wouldn’t be participating in beer kickbacks, the endless challenge of soothing fights between the white, male, working-class former clientele and the new counterculture bohemians and an early-70s recession spent telling friends that they couldn’t leave their seats until they’d found someone to replace them.

“Every revolution needs a good bar,” proclaims the inside jacket, and the Del was going to march dry, Republican Ann Arbor into the brave new world being ushered in by artists, beatniks, activists and musicians.

Harburg the social scientist takes us on a brief tour of the ground from which the Del Rio sprang. “In the prologue, I got to get into the cultural events that were sweeping the nation,” he said from his home in New York, where he’s lived full-time since the Del’s closing. “And I always — you know, they say, ‘Don’t trust anyone over 30,’ and I can almost say there’s some validity in that even today. It’s the spirit of the thing. Even though we were over 30, (co-writer) Eve (Silberman) once quoted me as being ‘counterculture before there was counterculture.’ And then the question is, what the heck is the counterculture?”

The civil rights movement, the women’s movement and dissent against the Vietnam War, he argues, were three of the broadest themes of the time — but he cites a less-studied fourth, a “challenge to authoritarian style and outdated institutional rules” which led to “a consensual approach rather than a chain of command and a line of authority,” that turned out to be play the most crucial role in the new watering hole’s constitution.

“I despised the reporters and older historians who were so prejudiced against the kinds of things that happened in terms of long hair and smoking and authority and made it into a stereotype,” said Harburg. “The mockery of the hippies; I despised that. As far as I’m concerned, the basis of the counterculture was the individual. The conventional and politically correct thinking which goes through the media and the academia and business is …not really saying what the counterculture is all about. They wouldn’t ever try it themselves.

“So in our little world of the Del Rio Bar, we responded to all these cultural, revolutionary changes that we wanted to have come about. The experiment … was a small group of people who put all that in action. Can we improve the democratic process? Prove that we don’t need a chain of command or authority? And I think it made a mark on the American culture.

"How do you run a small business on the basis of consensus? I say you experiment — nobody had any experience at that, particularly in a bar, and we figured things out as they do in science: by trial and error. If you’re smart about it, a good theory should last as long as the data that comes in from the experiment,” he finished with a laugh. “Then you go and learn something.”

So, for most of the bar’s history, any patron who demanded to see the manager would be told simply, “There isn’t one.” Although state liquor laws would only share licensing responsibility between four people, making the owners de facto leaders, the one firm rule at the Del became that “nobody could give anyone else an order.” Said Harburg, “Not even the customer, we felt, was giving an order — they were proposing to buy something, and there was a cooperation there at that level.”

The staff managed themselves at meetings held one Sunday a month, in which “anybody could say anything and everybody was expected to say something. And at the end, it wasn’t a majority rule. It was, ‘Does anyone disagree with that?’ What’s going on in the Senate today was set up by James Madison and designed to build consensus. But it’s been busted to hell and it’s not working like it should be.

“And for 35 years it did run, you know? So that’s what that book is about. I don’t know how many people are going to read it, but my wonderful first father-in-law, who was a remarkable man, said, ‘Even if nobody agrees with you, if nobody cares to hear you, put it on the record.’ So that’s what we did. We’re not proselytizing, but we made it work for that long.”

Actually, with grim interest I’d looked forward throughout the book to the description of the bar’s closing days, having heard one or two of the heated sides during that tumultuous stretch in late 2003. Harburg’s even-handed assessment offered plenty of blame to go around: the national recession of 2001, a sharp uptick in other downtown bars, the job-hopping of the prosperous 90s that led to a swollen payroll of temporary, “unacculturated” employees, a lack of informal leadership within the staff, the aging owners’ preoccupation with other concerns and a general dimming of all the counterculture ideals over time.

Some of the less savory events, like a picket line out front and vaguely threatening graffiti, apparently directed at owner Burgess’ wife, are described in a manner that, while perhaps succinct to the point of terse, doesn’t shrink away from full contact with the painful edges of this dying dream.

Some of us who are still occasionally have the absent thought, “You know, I’d really like to stop at the Del for a beer after work today,” before sharp cognizance pierces the reflexive memory may yet be wondering if that was the only possible ending to this story.

“There was one other thing that I didn’t put in the book,” Harburg said conspiratorially toward the end of our talk. “Years ago, back in the country of Yugoslavia before it broke down, I was taken around by the chair of the sociology department. And he had written a thesis about 20 to 25 factories that he’d been studying — it said in (Yugoslavia’s) constitution that the workers owned the factory, and he wanted to know how that worked in fact, so he collected data. So what happened was that the people who were doing the work elected the committee that would run (the factory). And there became a distance between the committee and the workers, because they elected people who were ‘leaders.’ (They were) a little different (from the workers), and it became a ‘we-they’ situation.

"So I thought, ‘How do you get rid of that?’ And I kept looking for it at the Del Rio, and it never happened. It was a little better because we all worked together, but there was still a ‘we-they’ that was never overcome.”

That “otherness” which sociologists tell us is at the root of every form of oppression, then, seems to be confoundingly difficult to root out, even by decree from the top — and keeping it at bay for three and a half decades by sheer dint of grassroots earnestness rings of triumph.

But the reason that every revolution needs a good bar isn’t to test out its organizational theories. It needs them for the same reason the rest of us do: to provide a little shelter and libation among like-minded souls, and, if you’re lucky, maybe a good story to wander through your field of vision by the end of the evening.

After trolling with Harburg through his pages of Del busts, jams, hijinks, parties, weddings and meetings, I couldn’t resist asking if he had one favorite tale that he loved telling better than all the rest.

“Oh, there are so many!” he laughed. “I have four sons and 10 grandchildren, right? I remember when I gave a talk (at the Ann Arbor District Library) about my father (lyricist) Yip (Harburg), and a little girl from the audience asked which of the songs was my favorite. My answer was that I have four sons, and I love them all the same, and that’s my answer here.”

You can get a copy of "Liberty, Equality, Consensus and All That Jazz at the Del Rio Bar" at local stores, Amazon.com or from Huron River Press.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

jeffsab

Mon, Mar 1, 2010 : 11:54 a.m.

Indeed, the book is as random and disjointed as the Del Rio was. But it's a great reminiscence of an era in which Ann Arbor was a much more interesting place. The AADL has a copy, and I encourage everyone who's moved here recently to read it.

Spooner

Mon, Mar 1, 2010 : 11:09 a.m.

I lived at The Del for 25 years. When I went to the book signing last fall, Ernie didn't recognize me, and I'm very distinctive. It was, however, great to see the former employees that attended.

ShadowManager

Mon, Mar 1, 2010 : 9:51 a.m.

I miss the Del Rio, especially their low bar tabs as they used to never bother switching one tab over to the next staff at shift change. If you ran up a tab with one bartender, just wait until they switched bartenders, and then ---presto!--- you were back to zero. It is no wonder at all that they went out of business with spotty accountung like that.

annarbor2233

Sun, Feb 28, 2010 : 6:28 p.m.

The Del was a great place, too bad it's gone. This book is poorly written and not worth the read.

David Briegel

Sun, Feb 28, 2010 : 10:22 a.m.

"The only place where everyone knew everyone else. Except you!"