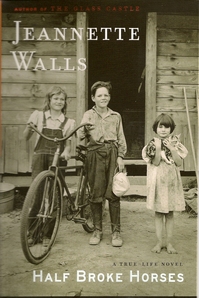

"Half Broke Horses": A Wild Ride Up the Family Tree

Smith was Walls’ maternal grandmother, and although her story is one that feels like it needed to be told for the good of all humanity, it actually only came to us because of Walls’ smashingly successful memoir, “The Glass Castle.” In that one, Walls —Â who comes to Borders for an author appearance on Jan. 5 — describes a chaotic and wandering childhood marked by lack of access to basics like heat and running water, led by two parents who clearly subscribed to neither the “children need structure” nor the “parents put their dreams on hold for the sake of the kids” philosophies of raising the next generation. But Walls pulled herself up by her bootstraps, graduating from Barnard College and embarking on a career in journalism that’s taken her from “Esquire” to “USA Today” to MSNBC.com, all the while being deliberately vague about a background she was sure would get her booted promptly out of polite society if it ever became public.

Funny how our deepest fears sometimes turn out to be just plain wrong. She wrote “The Glass Castle” at her husband’s insistence — he was sure that story needed to be told — and it got the warmest of receptions. People came out of the woodwork to tell her about their own bizarre pasts and unconventional upbringings, and far from feeling shunned by the civilized world, she instead found herself more deeply connected to the human condition than she ever thought possible.

Still, nobody really understood her mother, Rose Mary. So Walls, apparently born with the gift of taking lessons from hardship without letting it congeal into bitterness, would explain her mother’s upbringing in the barely-settled lands of Arizona and west Texas, where she and her little brother rode horses and shot slingshots at each other and rattled from town to town as their schoolteacher mother earned her own living teaching poor Mexican kids to read and write. “And (people’s) faces would just light up with what Lily would have called the ‘Eureka moment.’ My mother not only knew that you could live without electricity, she preferred it. I understand that she traded security for freedom.”

Several readers suggested that Walls’ next book should be her mother’s story, and she tried to tell it. But, she says in the author’s note, “as I talked to Mom about those years, she kept insisting that her mother was the one who had led the truly interesting life and that the book should be about Lily.” So over hundreds of hours, Rose Mary recounted Lily’s stories — stories she had heard again and again from the “passionate teacher and talker who explained in great detail what had happened to her, why it had happened, what she’d done about it, and what she’d learned from it, all with the idea of imparting life lessons to my mother.”

Although Lily died when Walls was 8, her memory was already vividly lodged in her granddaughter’s psyche. “Her life was this odd combination — there was a certain structure to it, but she was such a bombastic character. She never said anything, she shouted it. She was always dancing, singing, pulling out her gun, pulling out her choppers. I remember when she died, I knew the stability in my life was going with her, but she did what any good teacher does and that’s planting the seed. I felt I could do anything I wanted, because Lily said I could.”

Was there a story she heard at her grandmother’s knee that resonated particularly with her? “Oh, the story of taming the red devil,” replied Walls instantly, naming a two-page passage that had me falling off the couch in gleeful laughter when I read it. In it, a 27-year-old Lily is a month into a teaching post in Red Lake, Ariz. when two local yokels think they’re going to have a little sport with the city girl — she’d just returned from a rather miserable attempt to strike out on her own in Chicago — who’s come to give the youngsters a proper education. Telling her that she can pick up her paycheck as soon as she passes the simple test of riding a small but ornery-looking mustang in the corral next to the town hall, the two can barely contain their smirks in anticipation of delivering a little hard-knocks education of their own. So Lily, who started breaking horses when she was 6 and required only one good glance at the creature to know what she was in for, decided to simper a little and play along. The boys saddled up the horse while she found herself a good juniper branch, and then:

“The mustang was standing stock-still but watching me out of the corner of his eye. He was just another half-broke horse, and I’d seen plenty of them in my lifetime. I hiked up my skirt and shortened the reins, twisting the horse’s head to the right so he couldn’t swing his hindquarters away. … The way to stop a horse from bucking was to get his head up — he had to drop it to kick out with his hindquarters — and then send him forward. I popped the horse hard in the mouth with the reins, which jerked his head right up, and whaled his rump with the juniper branch.

"That got that little varmint’s attention — and the comedians’ as well.”

Two paragraphs later, she’d convinced the horse that his best course of action was to walk calmly under her command over to the two slack-jawed would-be pranksters who clearly had had their own troubles with him. “‘Nice little pony,’ I said. ‘Can I have my paycheck now?’”

Said Walls, “She just loved to tell that story — she hated the way the world underestimated her and she loved to prove them wrong. Sometimes a woman could do anything a man could, and sometimes they could do things men couldn’t.”

It’s nearly impossible to avoid comparing Lily’s ceaseless, indomitable grit with Walls’ own, and that was something she found exquisitely delightful about writing this story. “My mother would say, ‘You’re going to grow up just like my mother’ — and it was not a compliment. I can be a little willful or overdetermined at times. Everything in life is a blessing and a curse; that steeliness and toughness can get you through some tough times, but it doesn’t make you the easiest person in the world to live with and not the most sympathetic.

“I’m on a campaign right now to get people to explore our past, to talk to our ancestors. Sit down and interview them — these patterns do emerge. I like to say that if something seems inexplicable about your family, you just haven’t dug deep enough. You shouldn’t be a prisoner of your history, but it does explain a lot about who you are and where you are. In researching this, there were just so many ‘Oh my gosh, this explains a lot’ moments, and I think that’s wonderful.”

When I ask if she has any specific tips about digging up the family dirt, she laughs. “I think that if you just ask grandparents about their lives, you can’t get them to shut up. But I do find that sometimes the things you think are just fascinating are stuff they don’t even think of. Like the story of Lily’s 500 mile trek (as a teenager, alone on her favorite horse, trotting across the desert to her future in the teaching profession) — she and my mother were listening to the radio and there was a story about a woman who’d ridden 350 miles and she said, ‘Well that’s nothing. I rode 500 miles to my first job.’ And my mother just about fell off her chair, but Lily was like, ‘That’s just how we got around.’

“You could ask, ‘What’s your biggest memory?’ or ‘Tell me about the school you went to’ or ‘Tell me about your mother’s memories.’ ‘Tell me about your first job, the town you were raised in, how you prepared food, what happened when you guys hurt yourselves.’ It’s such a different world that people will be shocked by it. I think it opens the world to you. And I think most grandparents are delighted to talk about it.”

And please, please — if your family history turns up a gem like Lily Casey Smith, write us a book about it.

Jeannette Walls will read from and sign "Half-Broke Horses" at the downtown Borders at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan 5.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Barb

Thu, Jan 7, 2010 : 2:26 p.m.

I downloaded this for my Kindle by accident and was hoping I'd end happy that I did. Yay! Sounds like I will be.

Leah Rex

Wed, Jan 6, 2010 : 10:17 a.m.

I loved this book but love your review just as much. Excellent writing!

John

Mon, Jan 4, 2010 : 12:39 p.m.

This book was just great. One of the very funny instances is where she keeps taking out her false teeth to show everyone how beautiful they are........really cracked me up. What a woman, and her husband Jim is right up there too! Definitely worth a read.

pgeorgia

Mon, Jan 4, 2010 : 11:42 a.m.

I loved this book! I can't wait to meet her.