Concordia exhibit contrasts work of 2 local photographers in film, digital media

"Schooners" by Terry Abrams

Old-school darkroom photography meets brave new world digital photography in Concordia University’s Kreft Center Gallery “Photography: Digital and Film—Two Photographers, Two Processes, Two Visions.”

The photographers at hand are Washtenaw Community College photography instructors Terry Abrams and William Pelletier. And the contrast between their arts is telling — not so much for what is or is not the darkroom method; nor for the advantages or disadvantages of the digital medium.

If nothing else, it disproves the current notion in some quarters that art photography is a passing aesthetic because of the ability of digital media to make anyone with a camera an artist.

While it’s certainly true that digital photography has put the art form within the reach of anyone, the photographic aesthetic itself has ironically become more rigorous —Â in the same manner that any amateur can noodle on his musical instrument, yet it’s altogether another matter to master the instrument.

In darkroom photography, expense and expertise winnow the pretenders from the contenders because mastery requires some technical manipulation. It's a highly demanding sort of creativity.

The digital process — using flash memory cards in the place of emulsion film — has given any photographer a certain amount of freedom to capture his or her shot. But this freedom has also led to a heightening of standards. A privileged image — not to mention an additional resourcefulness in software and printing — is now the hallmark of the competent photographer.

“Photography: Digital and Film” compares and contrasts these two methods — illustrating their respective strengths while also highlighting the paths these two local masters have taken in their art.

Terry Abrams uses color digital photography to amplify his investigations in nature. Using the digital process to heighten his composition’s palette, Abrams takes advantage of nature as it presents itself to play digital effect against what he’s chosen to represent.

As such, Abrams’ photography often uses natural striation to maximize his artistry. Whether through rippling water (we’ll get to this below) or such striation as found in nature (for example, his “Dune Sonata” and “Twisted Dunes” in Death Valley or his “Sandstone Curves” and “Echo Canyon” in Utah), Abrams uses his palette, eye, and technical know-how to create graceful milieus of uncommon beauty.

This display particularly finds Abrams using the natural malleability of water to blend and separate his color patterns until the shades he uses serve as the element that anchors the composition. “Pilings, Lake Michigan,” for example, effectively uses interlocking striations of blue and pink undulating ripples washing upon recessed wooden pilings in the heart of the composition to illustrate reflections that give the appearance of broken wood jutting out of Lake Michigan.

Likewise, “Quiet Dawn, Turkey” has a similar orientation as the “Michigan” water work with the crucial difference of sharper contrasts between the pink and blue wavy lines. Myriad oscillating lines float horizontally across the composition. A solitary rowboat dramatically sits the center, but the work is a bravura interpretation of waterscape photography.

Finally, Abrams pushes the artistic envelope about as much as seemingly photographically possible as such in his “Harbor Colors, Belfast, Maine” and “Schooners, Camden, Maine” where the vertical oscillation of these photographs creates a chromatic cacophony reflected in the harbor water. Quite nearly the analog of impressionist painting, these expert photographs find Abrams masterfully painting with the same acuity that these earlier artists applied to their work through their pigments.

William Pelletier’s black and white darkroom photography almost seems mannered in contrast. Yet his artworks champion the surface texture of their materials as much as they use the technological advances of photography.

It would seem simple enough to say Pelletier’s work is a form of surrealism, but that doesn't go far enough. Pelletier’s photographs occupy a unique place in contemporary photography.

A hyper-realist at heart, Pelletier focuses intently on his compositional elements until his scrutiny heightens their appearance and they suggest otherworldly realms. This is not photography for the casual browser, because each composition presents a challenge to find hidden universes.

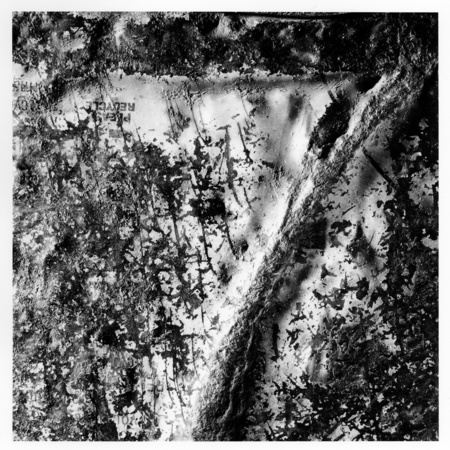

"In the Mountains, there you feel free" by William Pelletier

Pelletier uses black and white film stock to wrestle tableaus out of his fine-grained close-ups.

For example, “Monstrance’s” twisted piece of metal with two distended bolts for legs and pocked stone for head suggest a creature lying against a background. Pelletier adds subtle visual cues that give these varied surface qualities their anthropomorphic form.

“In the Mountains, there you feel free,” on the other hand, is apparently a piece of scrap cardboard or weathered plastic photographed at such close quarters, its diagonal striations look every bit like pine trees on a snowy slope. Pelletier’s created a miniature landscape out of otherwise disparate visual elements. Through the scrutiny of his camera, this diminutive scene has a life all its own.

But perhaps most spectacular of all, “Through the unknown, unremembered gate,” features a rusted metal base with a strategic rip running diagonally across the composition’s surface abetted by a black hole at the bottom. The photo is a vividly imagined visual metaphor evoking the bang of being emerging out of nothingness. Pelletier gives us an approximation of what the universe might have looked like at the initial birth of space and time. It's grand art in minute scale wrought through an expansive imagination.

“Photography: Digital and Film—Two Photographers, Two Processes, Two Visions” will continue through Feb. 20 at the Kreft Center Gallery at Concordia University, 4090 Geddes Road. Gallery hours are noon a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesday-Friday; and 1 to 5 p.m., Saturday-Sunday. For information, call 734-995-4612.

Comments

abc

Wed, Feb 2, 2011 : 3:47 p.m.

I will definitely be going to see these photos for myself but until then I would like to comment on this statement: "While it's certainly true that digital photography has put the art form within the reach of anyone…" If it is being implied that this is a new trend, putting the art form within the reach of anyone, I cannot agree. Many developments within the world of photography, since its inception, have been to lessen the cost, complexity and dangers of the process resulting in the widespread availability of the medium. Or to say it in another way, these developments put the art form within the reach of anyone. The Brownie was created more than 100 years ago as a simple and cheap camera for the masses." You push the button, we do the rest." When the 35 mm camera was becoming popular in the 1930's many photographers would not give up their large and medium format cameras. Photographers like Group f/64 even tried to separate 'serious' photography from the rest. (It is no accident that a 35mm camera does not have an f/64). Through the work of people like Cartier-Bresson, who embraced the 35mm camera early on, that 'serious' distinction blurred. And of course there is the Land Camera which made "polaroids'. This camera had many commercial uses since it was instant but was also a hit with the masses. Nevertheless photographers like Meyerowitz and Hockney, and artists like Close, also took advantage of polaroids and made some beautiful things with them. My point is that once flexible film, which was invented in the 1880's, became widespread photography has essentially been as available in one way, shape or form to anyone who wanted to try their hand.