Clements exhibit explores visual roots of racist stereotypes

Race and the power of art as social commentary collide in the exhibit “Reframing the Color Line: Race and Visual Culture of the Atlantic World, ” now on display at the University of Michigan William L. Clements Library.

The exhibit, co-curated by Martha S. Jones, U-M associate professor of history and Afroamerican and African studies, and Clements Library Curator of Graphics Clayton Lewis, pulls no punches in its study of 19th century African American cultural assimilation and the bigotry it engendered among other Americans.

The exhibit — consisting of original engravings, lithographs, watercolors, and books — is formidable not only because of the bias it reveals, but also because of the devastating pretension its caricatures offer. This is the most potent indictment to be found in “Reframing the Color Line.”

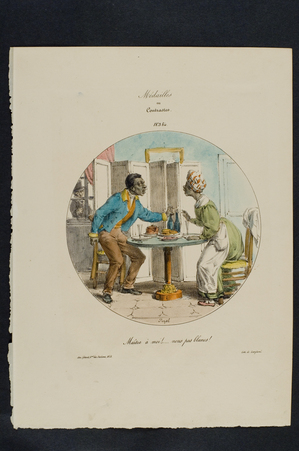

"Contrastes, Maitre a moi!... nois pas blancs" by Edme-Jean Pigal

Courtesy of the University of Michigan's Clements Library

Each of these European artists made careers out of ridiculing both the mores of their country’s middle class and the earthiness of their working class. They also influenced an American satirist, Edward Williams Clay, whose 1820s-1830s “Life in Philadelphia” etchings would follow in their path yet also be uniquely devastating in their scope and political influence.

As Jones and Lewis’ exhibition catalog tells us, “Clay’s ideas grew as much out of the artist’s engagements with his peers in London and Paris as it did from his encounters with African-Americans in Philadelphia.”

"Life in Philadelphia ('Going home from a tea fight')" by Edward Williams Clay

Courtesy of the University of Michigan's Clements Library

Clay used his considerable observational skills to craft a visual vocabulary that had tremendous influence through America’s mid-19th century. His cartoons reflected the dubious humor of many Americans in both the North and South who found the idea of black assimilation to be questionable at best — and ludicrous at worst. Clay mocks these aspirations through exaggerated physiologcal features as well as the ridiculous adoption of clothing and manners.

As Jones and Lewis’ exhibition catalogue says, “Clay’s ideas about race were quickly taken up by others. A countless number of 19th century engravers, lithographers, cartoonists, and illustrators adopted Clay’s visual strategies. They transformed what began as a local look at black life in Philadelphia into a national taxonomy of race.”

Clay’s ideas, conclude Jones and Lewis, “interwove social, political, and corporeal commentary on blackness, (and) dominated (American) visual culture’s contribution to national debates over race and power.” And the debate was sufficiently vitriolic as to stain American art well after the American Civil War through and considerably after Reconstruction.

Yet, ironically enough; the very observation that wounds can also be used to comment on the observation itself. Thus somewhat like the tactic of adopting of derogatory language to defuse bigotry, the exhibit concludes with 20th century examples of social satire — including a facsimile of Robert Colescott’s 1975 acrylic on canvas painting “George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware, Page from an American History Textbook” — that features caricatures even broader than of Clay’s in order to invert the negative imagery of racism.

“Reframing the Color Line: Race and Visual Culture of the Atlantic World” will continue through Feb. 19 at the University of Michigan William L. Clements Library, 909 S. University St. Exhibit hours are 1-4:45 p.m., Monday-Friday. For information, call 734-764-2347.

Comments

Teapot

Mon, Jan 4, 2010 : 12:04 p.m.

Those hours the museum is open are not very full-time working person friendly. I would love to see the exhibit but work 8-5. too bad.