Retired judge sets out to exonerate a former Michigan governor from Manchester in 'Wounded Warrior'

Michigan history pop quiz: Can you name the young, legless governor who followed his one term in office with a decade in the judiciary, then resigned from the Michigan Supreme Court after he was convicted of perjury?

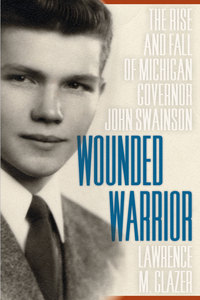

I couldn't either. But after reading Lawrence Glazer's “Wounded Warrior: The Rise and Fall of Michigan Governor John Swainson” (Michigan State University Press), I'm unlikely to forget it. The 2011 Michigan Notable Book and Independent Publisher (“Ippy”) gold medalist provides such a warm, thorough introduction that it's hard not to feel like you knew Swainson personally.

After a land mine during General Patton's advance blew off both his legs below the knee, he dedicated himself to attaining a law degree and then embarked on a rise through the Michigan Democratic Party that relies heavily on the word “meteoric” to describe it.

Losing his bid for re-election, he then bought a 167-acre farm near Manchester and set up a law practice, but when a Wayne County circuit judgeship opened up, his ambition and restlessness drove him right to it. It also propelled him to the Michigan Supreme Court five years later.

It was there that Swainson ran into John Whelan, on trial for his part in the robbery of a jewelry store in Adrian. Whelan was a career criminal whose practice of exchanging information about his accomplices for lighter sentences made him increasingly anxious to stay out of jail, where those accomplices and their friends would be likely to dish out a little justice of their own.

Just as things were looking pretty bleak for Whelan, bail bondsman Harvey Wish offered a deal whereby Wish's “friends” on the Michigan Supreme Court would keep Whelan out of the clink for a tidy little sum. Doing what he did best, Whelan took that offer right to the FBI.

Months of investigation ensued, then stalled, then reignited under a particularly zealous member of the U.S. Attorney's Office Federal Strike Force. Justice Swainson was eventually charged with one count of bribery and three of perjury, then acquitted of the former charge but convicted of the latter ones.

It's an exciting story by itself — the incompleteness of abbreviating it to the above paragraphs almost hurts — that becomes a thoroughly educational experience in Glazer's hands. The Lansing resident— w ho has been an assistant attorney general, chief legal advisor to Gov. James Blanchard and Ingham County Circuit Court judge — took up writing at the encouragement of his daughter, then a reporter for the Lansing State Journal.

“So I tried it, and I enjoyed it,” he said. He now contributes regular columns to DomeMagazine.com (and has traded careers with his daughter, who “thought this career in journalism might not work out, so she went to law school”).

Glazer's perspective on this story is delightful: He knows most of the characters personally, but treats them with evenhandedness. He is deeply familiar with the tedium-tending details on which our legal system turns, allowing his clear, patient prose to march us right through the muddy waters of everything from Michigan political history to rules about evidence admissibility. And his argument for Swainson's innocence is certainly thought-provoking and likely compelling.

Why, all these years after Swainson's 1975 conviction, did Glazer want to tell this story?

“The reasons changed as I got into it,” he answered. “Initially, I thought there was an interesting mystery — what really happened? And I wanted to reexamine the evidence in the trial, and any evidence I could find outside the trial, to piece together what really happened that led to his conviction. But as I read more about him, I also became more interested in him as a person, because his persona was very unusual. He was a very interesting person with an unusual combination of strengths and deficits.

“I've known a lot of politicians, including those who've held statewide office, and known them very well. Politicians who hold statewide office tend to be very cynical, because they've seen people at their rawest. And John Swainson didn't have that — he didn't have that at all. He was the only politician I know of who's held statewide office who was actually naïve about things. And I think it contributed in a large way to what happened to him.”

Swainson's long-time law partner puts it more bluntly in the book: “He never judged people. Which was a terrible mistake on his part.”

One of the most comforting and appalling aspects of reading history is the sense of deja vu. Swainson's electoral advantage is thought to be the fact that he's the candidate it would be “fun to have a beer with.” Partisan gridlock is referred to statewide as “the mess in Lansing.”

Michigan is in desperate need of economic revitalization. Business and labor interests are using the political system to fight about how to do it. A former Detroit mayor is in prison for financial wrongdoing. It's hard not to feel like the more things change, the more they stay the same.

“I agree,” said Glazer with a laugh, but then followed it by noting a procedural change with regard to grand jury testimony that may have made all the difference in Swainson's case.

He also added one more thing that looks different to him now: “I would say that one thing that's changed for the worse is that in the 70s, the Supreme Court got along pretty well. They might disagree, but as people, they could communicate. That does not appear to be the case today — it's pretty divided along partisan lines.”

Regardless of whether Glazer convinces you of Swainson's innocence, the story of his redemption is unmistakable. After a descent into despair that included two DUI busts and a rehab stint at the Veteran's Administration hospital in Ann Arbor, he lived out the rest of his life on the farm near Manchester and dedicated himself to his positions with the Ford Family Trust and the Michigan Historical Commission. I found myself moved to actual envy at the scene Glazer paints of his death.

“I would rather take a positive than a negative moral from this story,” said Glazer.

“We talked about Swainson's deficit, but he had this incredible ability to will himself back from horrible setbacks — the first was the loss of his legs and the second was the loss of his reputation and career, which he considered far more horrible, but he didn't quit. He was knocked off balance for sure; he drank, but he didn't let it beat him. And that's the thing to remember about him — that he was wounded twice, but not defeated.”

Lawrence Glazer's "Wounded Warrior: The Rise and Fall of Michigan Governor John Swainson" is available in bookstores and through Michigan State University Press.

Leah DuMouchel is a freelance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.