Michigan poet, funeral director Thomas Lynch turns to fiction for latest ruminations

As a longtime and vocal fan of Thomas Lynch, I’ve had many delightful opportunities to study audience reaction as I proselytize about his works. Usually the first thing a person does is check her hearing: “I’m sorry, I must have missed that last part — did you say ‘poet, philosopher and funeral director’?”

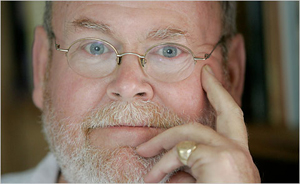

Thomas Lynch reads from "Apparition & Late Fictions" on Thursday at Nicola's Books.

Photo by Alan Betson

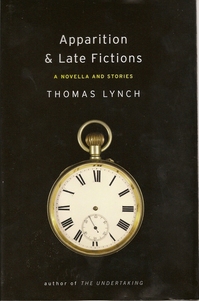

Yes. Yes I did. Lynch is one of the original “and sons” of Lynch and Sons Funeral Directors, which began with his father in Milford and has grown to include new Michigan cities and a new generation of sons. That a family in any business should have a poet in its midst is not so odd, but that a family of funeral directors should have a wordsmith unafraid to plumb both the horror and the certainty of extinction for a measure of peace is rather … blessed. He began with poetry, publishing the collections “Skating with Heather Grace” and “Grimalkin and Other Poems” before the nonfiction essays in “The Undertaking: Life Studies from the Dismal Trade” became a flagship work of both his careers. And in his 7th book, “Apparition & Late Fictions” (Norton), he turns to storycraft.

Why fiction this time around? “Seemed like the thing to do,” said Lynch easily by phone from a hotel in Ireland. He spends half his time on that side of the pond at an ancestral family cottage, although on this particular day he’d traveled a bit for a book festival and was soaking up a “breath of Cuba” from a brilliant west-coast sun. “I’ve always wanted to try fiction, and my working life has allowed for it now. I can get blocks of time to do it... I’ve always thought that characters and narrative need more workmanlike attention. Poetry and essays seems to be sort of ‘a la carte’ work you can do it in little bits — you can walk around for a long time with a poem before you have to write it down.”

The “Late Fictions” are the first four stories of the book, and each has a death that its other characters are in various stages of accommodating: a grown son who takes his father’s ashes fishing, a stunned funeral director and bereaved mother who sit helplessly together after a confluence of sport hunting and domestic violence has gone to its logical conclusion, an aging man who has outlived both his only daughter and the love of his life, a poet’s widow coming into her own glory.

The novella “Apparition” leaves the cessation of physical existence mostly aside to focus instead on divorce, that death of a family whose grief seems as if it should be slightly easier to bear but in fact occasions just as much shock, despair, recalibration and nakedness of the soul as the sort that requires one to wear dark clothes and buy flower arrangements. Each character gets Lynch’s unsparing sympathy — though his descriptions can be needle-sharp, he never veers into judgment, giving the impression of an acerbic-tongued and immutably loyal old friend. And each also gets his grace, of the sort that surely comes from his intimate communion with the grieving, when things have gone as dark as they’re likely to get and suddenly, impossibly, a moment of loveliness wrests a place for itself in the middle of it.

Three of the short stories feel like classic Lynch ruminations on the great intersection of life and death, and the portrait of marital dissolution he paints in the novella is so searing that I was fully convinced of its autobiographical elements before ever getting factual confirmation that Lynch, too, had raised his small children alone in the wake of an excruciating separation.

But one story did not start out as his at all: “Matinee de Septembre,” a retelling of German author Thomas Mann’s “Death in Venice” that’s set on Mackinac Island rather than Italy and against a backdrop of financial ruin rather than cholera. What drew him to that?

“I’ve always been an admirer of Thomas Mann and that story, and I’ve always admired the whole notion of being overwhelmed by beauty,” explained Lynch. “So when I was looking around for a story to finish the collection, I thought maybe as an homage to Mann, I’d take the elements and rework it with a different century, geography, gender.”

Was his choice to use a female narrator, poet (and University of Michigan professor) Aisling Black rather than male writer Gustav von Aschenbach, simply another altered parameter then? “I always wanted to have a female narrator, a female main character, to see how that worked... It seemed to me ‘Aisling Black’ and ‘Aschenbach’ could be twins in a way, the same but different. And I’ve often written poems that borrowed other poet’s vision or structure rather than creating some thing new.” In fact, this is something that the fictional Professor Black impresses upon her students, making the argument in a passage whose references echo against each other: “All art communes with all of the art that went before it. ‘It’s what we do,’ she’d say, quoting Auden, ‘to break bread with the dead.’”

I was interested in his choice of narrator because it seemed that a theme which might best be described by the made-up word “womanness” ran through this collection: lovers, widows, ex-wives, stepmothers, daughters and even a bitch (of the canine variety, although situated as it is among a litany of ex-wives, there’s no chance of escaping a connection). Asked if that was something he set out to explore, Lynch paused thoughtfully.

“No, but I’m glad you got that, because I think female characters are very powerful. … I think that most writers live in relation to other people, so it stands to reason that half of (their characters) are going to be women. I think they’re very strong characters, and they have rich internal lives. The character in ‘Hunter’s Moon,’ whose daughter is killed or a suicide or an accident, I think that’s fairly emblematic of most men’s relationships with many women — that they just can’t know the internal lives of women, although they spend a fair amount of time trying to suss it out.”

I found the depth of Lynch’s “sussing” to be surprisingly revealed when two characters, both ex-wives in different stories, spoke a few phrases I knew verbatim from my women’s studies minor and have heard nearly nowhere since. Along the “patriarchy” and “duped by the culture into marriage and babies” lines, they’re not phrases that all men use fluently, and the precision with which they were wielded made my eyebrows spring up. Where’d he hear that? I wondered. In the Interviews section of his Web site, he’s quoted as saying, “I was a single parent for a long time, which I think, for men, makes them feminists.” But while sudden and unremitting laundry/dishes/dinner/homework/carpool duty might leave a person with new revelations about feeling duped, it’s unlikely to introduce the word “patriarchy” into one’s vocabulary — is he also one of the rare men who trucks in a more academic feminism?

“I think I’ve had some of both, and I’ve found the academic feminism very — and this is true of any sort of scripture — you find it very interesting in text and very disappointing in practice,” he said. “If you read St. Thomas Aquinas, you get a great sense of life, but if you look at the Catholic church, they haven’t a clue about living. It’s the difference between the idea of thing and the thing itself — there’s a lot of slip between the cup and the lip, as they say.”

And in the case of the main character in the title novella, Adrian Littlefield, the thing itself was that after one woman used those words (and a host of other things) to rend his family apart, a shipment of manna and balm for his soul arrived from another woman unasked and uncompensated.

“I just think the character of Adrian has experienced women in all different ways, and I think he’s not sure which is the most genuine. He clearly experiences grace through the character of Mary De Dona — and I guess that’s one of the things I wanted to explore, that we see goodness in the s--- that happens, rather than the new baby and the sunset and the bride and groom. (Those things are lovely), but my own experience has taught me that we better go looking in the s--- that happens as well, because a lot of (that) happens — if we’re ever going to balance the accounts of goodness and badness, we better seek evidence (for the good) in turmoil and disaster.”

Thomas Lynch will be at Nicola's Books to read from and sign "Apparition & Late Fictions" at 7 p.m. on Thursday, March 25.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Mary Bilyeu

Sat, Mar 20, 2010 : 11:12 a.m.

I am looking VERY forward to attending!