"Tradition Transformed" at UMMA a striking showcase of Chinese painter Chang Ku-nien

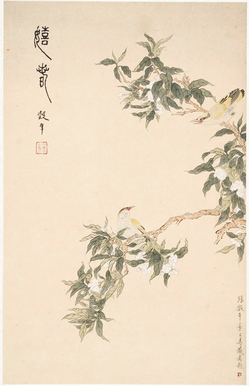

"Songbirds in Spring" framed scroll, ink and color on paper by Chang Ku-nien. On view in "Tradition Transformed" at UMMA through April 18, 2010.

Image courtesy UMMA

Chang Ku-nien’s stunning retrospective in the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s spacious A. Alfred Taubman Gallery accomplishes its considerable task: “Tradition Transformed” provides striking examples of his aesthetic as it steadily evolved during a sensational period of Chinese history.

Chang’s lifespan, 1906-1987, covers the pivotal transitions of China’s 20th century. During the course of his life, Chang lived through the fall of the 2½ century Qing dynasty in 1911; the revolution establishing the Republic of China; Japan’s absorption of Manchuria as Manchukuo in the 1930s; as well as the subsequent People’s Republic of China, effecting his 1949 resettlement in Taiwan.

And as if this wasn’t enough, Chang later chose toward the end of his life to resettle in Flint and continue to paint while living with his son, Cheng-Yang Chang, who has in turn donated some of Chang’s most powerful paintings to the UMMA’s permanent collection.

The most marvelous thing about this sweeping exhibit is its contrast between Chang’s artful discipline and how he reacted to China’s unceasing social, cultural, and political turbulence. Its pastoral calmness seems the exact opposite of this turbulence. As the UMMA’s gallery statement tells us, even as his training seemingly looked back, his temperament was always casting his art forward.

“Literati painting,” says the gallery statement, “(as) one of the most celebrated traditions in Chinese art, was historically intended to be created in the leisure time of educated men whose professional lives were dedicated to public service.”

As a “literati” painter (ending his career as a banker in Taiwan), Chang always painted as he chose. And it’s this inclination towards subtly bending the tradition he absorbed with his preference towards artistic freedom that ultimately shapes his career.

For, as the UMMA’s gallery statement then adds, ostensibly as an amateur, he was freed “from the constraints of the marketplace” (the whole point of being a “literati” painter) and Chang was thereby able to produce art that expressed “1st and foremost his intellect and emotions.”

The statement then concludes, “Chang trained as a literati painter in Shanghai in the 1920s and 30s, which meant studying not just painting, but calligraphy, and classical literature — all fundamental elements of a traditional artist’s education.”

And it’s ultimately this remarkably passionate, yet highly ordered intellect that’s on display in the 66 magnificent paintings, hand scrolls, and hanging scrolls constituting this retrospective. This display unlocks the essence of a cultural tradition while reflecting the artist’s will.

For example, Chang’s “White Clouds and Red Trees,” a 1926 ink and color on paper hanging scroll drawn from early in his career, illustrates his careful study of the traditional brush technique in the style of Wang Jian, one of the masters of the 16th-17th century Qing dynasty. Chang faithfully emulates Jian’s sinuous brushstroke through his careful composition of 2 tree-laden rocky ridges. The work is not only an homage to one of the greatest Chinese painters, but it is also a noteworthy departure for his evolving style of art.

On the other hand, 1 of the more noteworthy aspects of “Tradition Transformed” is the art that gives us a glimpse of Chang’s personality beneath the trained formality. And these paintings — vastly more intimate in scale — fall into the category of art studies and personal gifts.

Among these studies are a series of smaller-scale works commissioned in 1970 (and afterward, revised and published as a painting manual a decade later) that provide analysis and illustration of Chinese landscape painting. Chang carefully details the execution of brush techniques; color wash application; and the art of crafting from small scale objects to overarching composition in his “Painting Trees,” “Blue and Green Technique,” “Painting Clouds,” and “Painting the Three Distances” — all marked by an attention to custom as well as innovation.

Likewise, 2 similar small-scaled color and ink on paper scroll 1978 paintings — “Two Boys Playing” and “Bob Buddha” — give the exhibit a glimpse of Chang’s personal life. “Two Boys Playing” features 2 lively youngsters capering about a tree. It was painted for Chang’s daughter’s mother-in-law. And “Bob Buddha” — a whimsical interpretation of the famed spiritual teacher — is painted as a portrait of her father-in-law. Both artworks reflect a respect for tradition while also playfully reinterpreting those traditions for contemporary purposes.

Interestingly, the opposite is the case for an exquisite framed ink and color on paper scroll “Songbirds of Spring” — an example of China’s “bird and flower” genre — where precision in both hand and eye are harmonized to its subject matter. Chang’s painting of the goldfinches in this painting (as well as their placement on flowery camellias) is done in the famed “gongbi” style of 10th century Chinese painting, in which objective fidelity is supposed to be matched with a highly detailed brushstroke.

Ultimately, however, “Tradition Transformed’s” considerable strength lies in the many oversized wall-mounted scrolls that stretch across the length of the UMMA’s Taubman Gallery. And of these many artworks, 2 multi-part wall scrolls — 1965’s 6-part “Ali Mountain based on Sketches 1-6” and 1967’s 4-part “Taiwan Cross-Island Highway” — are easily the signature masterworks of this exhibit.

Both paintings employ a calligraphic landscape curvature whose sweeping ink washes give the viewer the exhilaration of taking in the world at a single view through multiple perspectives. ““Ali Mountain” is a tour de force with its foreground range receding stunningly into the work’s smoky background. And “Taiwan Cross-Island Highway” carries this impulse forward with its shifting perspectives alternating between minute observation and leaps of far-ranging imagination.

Finally, Chang’s affection for the Great Lakes is to be found in his handsome 1975 “Autumn Colors on Michigan Lake,” where the choppy waterline is evenly synchronized by his interpretation of our state’s famed Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore. A bold calligraphic line sketches a hiker’s path rimming the weather-sculpted cliffs above Lake Superior. Tracing off into the work’s background, this fluid line speaks of Chang’s artistic training — as well as his power of observation, abiding affection, and resolute spirit — placed in the service of one of Michigan’s most remarkable natural splendors.

“Tradition Transformed: Chang Ku-nien, Master Painter of the 20th Century” continues through April 18 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 South State Street. Museum hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Wednesday and Saturday; 10 a.m.-10 p.m. Thursday-Friday; and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.

John Carlos Cantú is a free-lance writer who reviews art for AnnArbor.com.