University of Michigan presenting powerful, intriguing exhibit on the Emancipation Proclamation

“A Stag Dance. Four Hands ‘Round” from “Down in Dixie” Vol.4 by Stanton P. Allen

courtesy of the University of Michigan

And as “Proclaiming Emancipation” at the University of Michigan Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library Gallery and Audubon Room shows us, it’s also one of the first journalistic mass-media sensations that shaped the public opinion of its time as much as it’s shaped American life afterward.

Co-sponsored by the U-M Graduate Library and U-M William C. Clements Library, the exhibit examines the effect this unprecedented presidential act had (and still has) on American fact and tradition.

As Mary Morris, U-M Hatcher public information specialist, says in her press release of the exhibit, “The Proclamation accelerated a massive human migration towards freedom, opened the door to the enlistment of black men in the Union Army, and marked a significant shift in executive power. Today it remains a powerful near-sacred artifact in our collective memory.”

Indeed it does.

The proclamation was an executive order set for January 1, 1863, setting all persons bound by slavery free in territories rebelling against United States authority during the American Civil War. It therefore had no congressional authority as law. Rather, it was a presidential act giving the union military the power to treat indentured peoples as freedmen in the 10 Confederate states in rebellion on that precise date.

As such, it was a highly controversial executive action that its opponents claimed was a clear presidential overreach whose goal was to make the destruction of slavery as much a goal of the American Civil War as reuniting the Union itself. Strong in moral and presidential suasion, what was lacking, according to its critics, was the legal authority to outlaw involuntary servitude. It would take the 13th amendment to the Constitution to clear this legal hurdle.

These facts, then, are the clear political grounds.

Exhibit organizers Clayton Lewis (curator of graphics at the Clements Library) and Martha S. Jones (professor of history, Afroamerican and African studies, and law) have added to the display the personal and social dimensions of the proclamation, as well as the print influences that tugged at public opinion at the time.

As Jones told Kevin Brown, associate editor of the University Record, in a Nov. 5 interview, “The proclamation represents a critical turning point about the powers of presidents, especially in wartime. Lincoln used his authority as commander-in-chief to issue the proclamation, just as he had earlier in the (civil) war to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. He was widely criticized for this and many believed he had overstepped. That question, about the power of the president to act unilaterally and without the consent of Congress, particularly in times of war resonates with us today. The origins of that debate are in the Emancipation Proclamation.

“We hope to debunk some myths. The proclamation did not ‘free the slaves.’ Nor did Lincoln accomplish this alone. The meaning of a legal text such as the Proclamation goes far beyond its formal terms. The exhibit explains how the proclamation was understood, interpreted from many perspectives. Emancipation was a lived experience, not a piece of paper.”

Indeed, one of the most fascinating elements of the exhibit is a wall dedicated to illustrating a half-dozen vivid renderings of the proclamation through vastly different fonts, formats, and graphics. Each 19th century printing repeats verbatim the proclamation’s words, but the manner in which these printers handle the substance of the text are imaginative in their enthusiasm.

In a similar manner, the Gallery display has mounted a historical timeline running from American revolutionary times through the 1888 abolition of slavery in Brazil; thereby placing the proclamation in its proper historic position.

As the display’s gallery statement then tells us, “‘Proclaiming Emancipation’ explores these views through the holdings of the Clements Library, with select items from collaborating institutions. Letters, sketchbooks, diaries, pamphlets, manuscripts, books, memoirs, prints, photographs, broadsides, and ephemera, all capture reflections upon the Proclamation and the meaning of emancipation.”

All these mass-media journalistic efforts are front and center, with facsimiles running the length of the spacious Hatcher Gallery walls . Original artifacts are mounted in the more intimate Audubon Room.

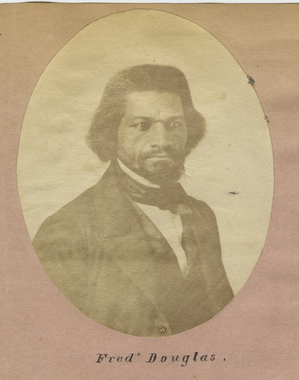

"'Fred' Douglass"

courtesy of the University of Michigan

A facsimile of Theo. Leonhardt’s 1861 “Map Showing the Distribution of the Slave Population of the Southern States of the United States. Compiled from the Census of 1860 (with added tinting showing the areas where the Emancipation Proclamation was in effect, January 1, 1863)” uses detailed demographics to show one viewpoint of the proclamation, while Adalbert J. Volck’s 1882/1884 engraving “Confederate Civil War Etchings” caricatures President Lincoln forcibly stepping on a copy of the Constitution long after the event.

All the more reason this balanced, yet nuanced display seeks to ground this historic event in its proper context. For one of the texts on display—Thomas Wentworth Higgison’s 1870 memoir, “Army Life in a Black Regiment”—forcefully evokes the moral significance of Lincoln’s work. And in doing so, it sweeps away any uncertainty as well as highlights what significance followed.

Higgison writes, “The President’s Proclamation was read by Dr. W.H. Brisbane…. Then followed an incident; so simple, so touching, so utterly unexpected and startling, that I can scarcely believe it in recalling, though it gave the key-note to the whole day.

“The very moment the speaker had ceased, and just as I took and waved the flag, which now for the first time meant anything to these poor people, there suddenly arose, close beside the platform, a strong male voice (but rather cracked and elderly) into which two women’s voices instantly blended singing, as if by impulse that could no more be repressed than the morning note of the song-sparrow.— ‘My country ‘tis of thee/Sweet Land of Liberty/Of thee I sing!’”

“Proclaiming Emancipation” will continue through Feb. 18 at the University of Michigan Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library Gallery and Audubon Room, Room 100, 913 S. University St. Exhibit hours are 8:30 a.m.-7 p.m. Monday-Friday; 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Saturday; and 1-7 p.m. Sunday. The Graduate Library will be closed for its seasonal break Dec 22-Jan 1. For information, call 734-764-0400.

Comments

arborani

Tue, Nov 27, 2012 : 3:11 p.m.

"Fred" Douglass was one impressive-looking dude.

Jeffersonian Liberal

Tue, Nov 27, 2012 : 1:23 p.m.

It would be nice if they would point out to the revisionist historians that the tyrant Lincoln didn't free the slaves. The slave owners in the Union States, especially the border states were not pressured to free theirs.

Epengar

Tue, Nov 27, 2012 : 3:48 p.m.

If you read more closely, and didn't just post to grind your axe, you'd see that the article says just that: "As such, it was a highly controversial executive action that its opponents claimed was a clear presidential overreach whose goal was to make the destruction of slavery as much a goal of the American Civil War as reuniting the Union itself. Strong in moral and presidential suasion, what was lacking, according to its critics, was the legal authority to outlaw involuntary servitude. It would take the 13th amendment to the Constitution to clear this legal hurdle."