Landmark print exhibit at UMMA illuminates contemporary Chinese art and society

"Darling of the Times" by Liu Qingyuan

Featuring 114 artworks by 41 leading printmakers from contemporary China, “Multiple Images” fully uses this space—easily our area’s most handsome forum for the visual arts—to its fullest. Indeed, the exhibit is so bountiful, it spills over to an adjacent space down the hall.

As the UMMA’s gallery statement tells us, the exhibition features work “by such artists as Xu Bing, Kang Ning, Song Yuanwen, Chen Qi, He Kun and Fang Limin, as well as many other accomplished printmakers.

“Curated by Xiaobing Tang, Helmut F. Stern professor of modern Chinese studies at the U-M, and organized by the museum with the assistance and cooperation of the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, China, the exhibition—the largest examination of contemporary Chinese prints in the U.S. since 2000—provides an important framework for understanding both contemporary art from China and contemporary Chinese society.”

This it most certainly does. For “Multiple Images” is one of those oversized affairs whose very richness is its most significant conceptual thread. The exhibit features art that appeals to one audience or another even as it illustrates broadly related tangents.

From traditional scrolls running across the expansive Taubman gallery to the use of multimedia to supplement abstraction, the exhibit features woodprint application on a superior scale. With broad categories such as portraiture (called “Fellow Beings”); landscape genre (“Old and New”); and “Layered Abstractions,” the exhibit’s just as expansive in its subject matter as it is in its presentation.

As Tang says of his effort, “In the course of the 20th century, the woodblock print evolved from a native art form long associated with religious scripture, book illustration, and folk rituals into a vital part of modern China’s artistic language. When the first public exhibition of modern-style woodcuts took place in Shanghai in 1931, it heralded a dynamic art movement that helped shape the course of Chinese social, political, and cultural history.

“The title ‘Multiple Impressions’” refers first to the process of repeatedly inking and printing a block to make copies—the essence of printmaking; it also points to the array of styles, techniques, and innovations transforming the art of printmaking in China today.”

This clash of tradition and innovation is best seen in the exhibit’s landscape section, because the tradition of the genre runs so deep in this culture, it invites invention and experimentation.

Xu Bing’s multi-block woodcut “Mustard Seed Garden Landscape Scroll” is easily the display’s most magnificent artwork. Expansive and languorous, its rocks, trees and water depicted through concise lines cascading upon each other constitute an endless panorama devoted to the reverence of nature found in traditional Chinese society and art. Not an imitation of the past, but most certainly homage to tradition, Xu’s 2009-10 scroll depicts the utmost of both Chinese convention as well as the country’s transforming aesthetic.

Moving within the range of 20th century modernist expression, yet also paying respect to China’s formidable landscape antecedents, He Kun’s 2009 “Song of Spring” is an optimistic tribute to both East and West. A member of the Yunnan school of printmaking, he obsessively works his woodcut surface to redraft the print, creating an almost unruly spray of color that’s both vitally energetic and visually dynamic.

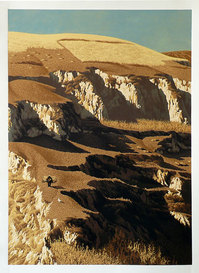

"Bright Autumn" by Li Yanpeng

The exhibit’s “Fellow Beings” section is the most visually variable. These prints most fully explore the social and political convolutions that have made China the nation it is today.

Yu Chengyou’s 2007 multi-block woodcut “Nice Day” shows a worker sitting at rest in a rich field of lettuce. Yu’s print champions labor even as he skirts visual representation through the multi-block printmaking technique. In a country where social realism was championed as the people’s aesthetic for decades, Yu broadens the articulation of his cut to make the work acceptable to the masses yet artistically innovative.

Not particularly interested in being socially acceptable, meanwhile, Liu Qingyuan's wry 2009 woodcut “Darling of the Times No. 4” is as much pointed commentary as it is portraiture. The print, depicting a bellicose youth, is both caricature and pointed critique, as Liu's nonconformist youngster is carved out of thickened line with his squelched face signaling displeasure—coupled with a tense appearance that makes him a hardnosed example of China’s youth today.

Of the exhibit’s three sections, “Layered Abstractions” is easily the most nuanced and ambiguous. It’s also the most courageous given that China, like many other socialist states, has waged an unceasing war on modernism and abstraction in particular. In a country that had an official contempt of art for art’s sake, these works are easily the most daring on display.

"Notations of Time No. 5" by Chen Qi

“Notations of Time: Black Book,” a 2010 handmade book (with calligraphy by Xu Bing) houses this series of prints with its biomorphic squiggles cutting through from page to page. Likewise, Chen’s “Notations of Time No. 2” experimental video leafs through the book to take advantage of it incised relief. And finally, Chen’s circular “Notations of Time No. 5,” a 2007 multi-block woodcut, contrasts the purity of the circle against these biomorphic squiggles in varying monochromatic shades. Working beyond the traditional purview of Chinese art, Chen creates a slightly surreal, bravura abstraction that resolutely lives on its own terms.

“Multiple Impressions: Contemporary Chinese Woodblock Prints” will continue through Oct. 23 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. Museum hours are 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Tuesday-Friday (starting next week, to 10 a.m.-5 p.m.); 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday; and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.