UMMA 'Flip Your Field' exhibit takes a fascinating look at concept of horizons

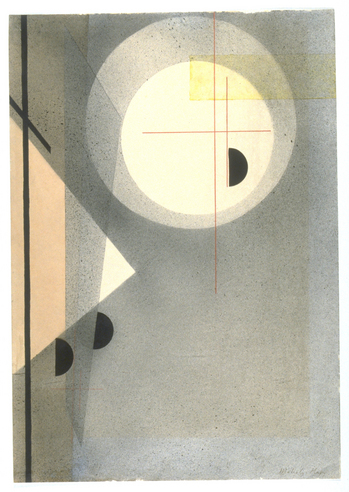

"Abstract Composition (Abstrakte Komposition)" by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

University of Michigan Museum of Art

In this instance, U-M Professor Celeste Brusati of the U-M’s departments of Women’s Studies and History of Art; as well as the U-M School of Art and Architectural Design, has chosen to go well beyond her professional interest in 17th century Dutch art. Brusati has chosen to “flip her field” by crafting a UMMA exhibit consisting of 20th century UMMA abstract prints that seemingly contrast with her interest in realism.

Seemingly contrast—but not quite. For as Brusati says in her curator’s statement, “I believe all figuration involves abstraction; one has to abstract in order to make a very precise, naturalist, realist image, we just don’t recognize it as such.

“Certain Dutch artists central to my research, notably Johannes Vermeer and Pieter Saenredam, are abstract in many ways. Rather than treating them as modernists before the fact, I try to understand the abstract dimensions of their art in relation to artistic concerns of their own time.”

“I have been thinking about horizons a lot,” continues Brusati, “and what caught my eye right away were those (UMMA) prints with very tightly designed, very rectilinear, carefully framed compositions. When we look at any array of lines and colors on a surface, we tend to look for orienting vectors, like horizons.

“I was particularly attuned to horizons because of their importance in northern European perspective theory and practice, especially in pictures that have many focal points, eccentric vanishing points, and variable horizon levels, from bird’s eye to worm’s eye views. I suddenly realized that there were a number of 20th century abstract artists who were making the horizon a subject, and that set me on my way.”

Brusati’s keen insight certainly sets us on our way, because this exhibit might as well be subtitled “horizon.”

Part of the profound novelty of this exhibit—consisting of accomplished work from such 20th century masters as Josef Albers, Lee Bontecou, Helen Frankenthaler, Wassily Kandinsky, Ellsworth Kelly, Joan Miro, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Robert Motherwell, Kenneth Noland, Theodoros Stamos, Antonio Tapies, and Takeshi Takahara (among many others)—is seeing gems from the UMMA’s permanent collection that are rarely shown to the public.

Yet it’s also taken a scholar of Brusati’s acumen to choose abstract artworks that so clearly feature horizons; although what constitutes a “horizon” differs from work to work.

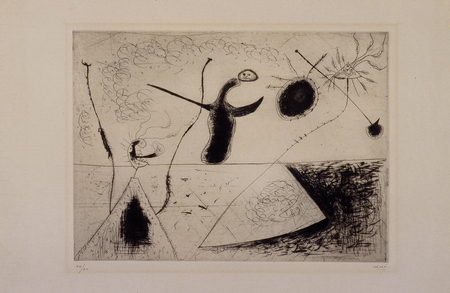

The pedagogical aspect of “Flip Your Field” more than fulfills its function. For what constitutes a horizon for Frankenthaler is going to differ from what constitutes a horizon Albers. Just as what it means for an artwork to be abstract is going to differ radically from Moholy-Nagy to Miro.

"The Skyline (La Ligne d'Horizon)" by Joan Miro

On the other hand, notice Brusati’s choice of Josef Alber’s handsome, less-is-more 1958 intaglio on paper “Duo S-Z.” This tidy classic is a cream-colored sheet of paper upon which geometric rectangles have been embossed as intersecting cubes. This work features a barely perceptible horizon that’s not only the artistic equal of Alber’s famed “Homage to the Square” series, but more cleverly—there’s certainly a “Duo S-Z” if you can find it.

Finally, the single work here that best illustrates Brusati’s interest in horizons is likely Antonio Tapies’ 1969 lithograph painted in two colors “L’Horizon.” This surprisingly simple, aptly named lithograph of a two-toned red swipe running 43 inches across the composition combines a slashing muscular gesture with the outward tension necessary to create a particularly active perspective. Tapies’ “L’Horizon” not only forcibly flips its field; it lashes forth happily with a primal vigor that passionately galvanizes the print’s surface.

“Flip Your Field: Abstract Art from the Collection” will continue through Sept. 2 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. Museum hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.

Comments

mixmaster

Fri, Jul 6, 2012 : 1:16 p.m.

This is roots art. Now it can be seen where all the copiers get their inspiration.