UMMA hosting thought-provoking video installation from South Korean art collaborative

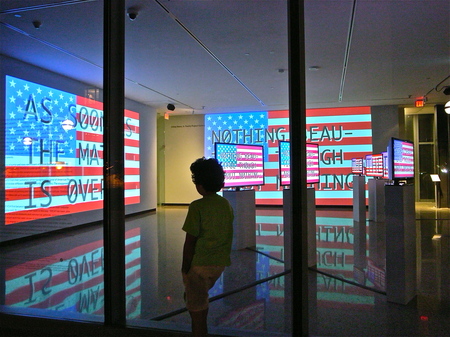

The YHCHI installation at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

courtesy UMMA

Formed in 1998, YHCHI is two artists—South Korean artist and translator Young-Hae Chang and American poet Marc Voge—whose concrete poetry (as the UMMA’s exhibition statement tells us) exists "at the nexus of visual art and digital literature.”

As the statement continues, “Blurring the boundaries between media, technologies, and cultural histories, YHCHI has gained international acclaim for their ‘net art’ productions; mostly black-and-white videos of quickly flashing capitalized text in a generic font with synchronized music.”

That pretty much describes it—with the sole exception that Ann Arbor’s getting a double-dose of this group’s on-site humor set to 6 synchronized video monitors of ascending size, as well as being screened on two gallery walls with vivid stars and stripes set as the poetry’s background.

An image from the YHCHI installation.

courtesy UMMA

"Like pioneering video artists in the 1970s," continues Oyobe, YHCHI’s art "is both socially and culturally critical. Though a number of discursive modes are used—monologue, dialogue, personal letters, speeches, prose, novels, poems, journalism, and chat room posts and responses—the result is usually a narrative with a linear chronological progression that remains coherent despite gaps.”

Clocking in at a brisk 11 minutes each, the two halves of this pointed, coordinated video installation (crafted specifically for the UMMA) give us high and low doses of YHCHI’s signature irony.

“PART ONE: “WANT TO DO GOOD? KNOW HOW TO SHOOT A SEMI- AUTOMATIC HANDGUN?”—the all-caps is part of the artists' signature—is ghost written by “Winnie Kong” in a manner reminiscent of unsolicited email missives asking something of the recipient. In this instance, Kong is supplicating assistance for clinics in Africa whose needs and challenges are so stark it’d take an extraordinarily dedicated person to volunteer—all this above the seemingly pointed prerequisite of needing a handy handgun to protect oneself while doing the job. Philanthropy has never seemed so harrowing—although it’s undoubtedly always near just that—and YHCHI intends to remind us. Indeed, this is social satire of the understated sort that vaguely echoes in its way Jonathan Swift’s famous 1789 “Modest Proposal.”

Racing across the Stenn, Jr. Family Gallery south wall (as well as three aforementioned video monitors), “WANT TO DO GOOD? KNOW HOW TO SHOOT A SEMI- AUTOMATIC HANDGUN?” is a stark reminder that sometimes doing good isn’t always good for one’s health.

Likewise, flashing across the gallery's east wall (as well as three other monitors), “PART TWO: “BEING AND NOTHINGNESS AND BEING MIDDLE CLASS” is far more abstract in its deflation of social and economic identity.

Pointedly using existential ontology against itself, the video reads like social analysis gone wrong. But it’s actually an exceedingly clever monologue reminding the viewer that most Americans think of themselves as being “middle class” in personal identity. YHCHI then seeks to undercut this notion by making pointed reference to those of a smaller, more privileged class whose wealth is now committed to appearing middle class—while also maintaining its perks.

It’s all in an ironic day’s work because YHCHI’s electronic art, says Oyobe, “often confronts the viewer with stark contrasts—the grand and the mundane, official history and private story, violence and tranquility, sacred and profane, and international and local—at high velocity and with a brilliant sense of humor and irony reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp, whom they consider an important influence.”

OK. But then YHCHI, like Duchamp, is having a good laugh elsewhere. Because as this mordant electronic poetry seeks to remind us: Having the last laugh is always the best laugh—unless there’s really nothing to laugh about at all.

YOUNG-HAE CHANG HEAVY INDUSTRIES will continue through Dec. 30 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. Museum hours are 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday; and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.