How does he think of THAT? "Jumanji" author Chris Van Allsburg coming to UMMA

Chris Van Allsburg

Actually, you can get the answer to the query in the title of this year’s Sarah Marwil Lamstein Children’s Literature Lecture, “Whose Little Dog is That? A Reflection on the Various Sources of Inspiration for the Idle Storyteller,” in the very first FAQ on presenter Chris Van Allsburg’s Web site: The adorable, floppy-eared Fritz, who crops up in every one of Van Allsburg’s books (“The Polar Express” and “Jumanji,” to name just two) turns out to be a bull terrier that Van Allsburg talked his brother-in-law into getting so that he’d have an interesting-looking model for the dog he was drawing in his first book, “The Garden of Abdul Gasazi.” The brother-in-law agreed, which made Van Allsburg feel like an uncle of sorts to the pooch, so when an accident “sent him to the big dog kennel in the sky at a young age,” Van Allsburg decided to honor Fritz’s contribution to his first book by including a little piece of him in all the others.

Addressing the second part of the lecture’s title, though, promises to take up the full hour-long lecture and could probably spill over into several more just like it. I mean, we’re talking about a collection of stories that includes a witch with broom trouble, a little sister hypnotized into dogginess, a dentist who gets paid in magical fruit and an alphabet play in 26 acts. And although the Web site gives a couple of choice tidbits — the genesis for “Two Bad Ants,” for example, was a moment spent pondering the journey that two bugs frolicking on a kitchen counter must have taken in order to arrive there, and a purple-and-green, terrified-looking Princess Tiger Lily in his daughter’s “Peter Pan” coloring book gave rise to the puzzled characters in “Bad Day at Riverbend” — he quickly goes on to note that these little gems are just the starting points.

“The kind of story a writer ends up telling, such as a scary story, a funny story, a sad story, or an exciting story, is not the result of the little idea that starts the writer thinking. The kind of story a writer ends up telling is the result of the kind of person that the writer is.”

It’s tempting after a statement like that to go rummaging around in Van Allsburg’s stories for guesses about what kind of person he is, but since he’ll be here soon to give us the definitive answers, we can start with an adjective that’s free of guesswork: “well-loved.”

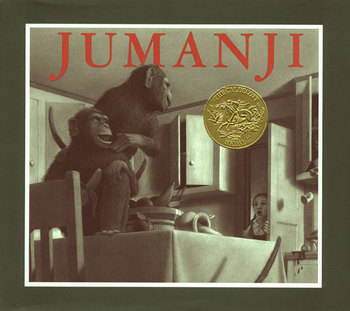

That first book, published in 1979, was immediately given an American Library Association Caldecott Honor, and within the next seven years he’d taken the top-prize Caldecott Medal twice: for “Jumanji” in 1982, and for “The Polar Express” in 1986. Both were turned into major motion pictures, as was “Zathura: A Space Adventure,” a sequel of sorts to “Jumanji.” “The Wreck of the Zephyr,” “The Mysteries of Harris Burdick” and “The Stranger” were all New York Times Best Illustrated books. And nearly every title he’s penned has a lesson plan devoted to it somewhere on the Web.

This makes all the more remarkable the fact that writing books wasn’t Van Allsburg’s first career choice — or second, or third. His early visions of a career in law disappeared almost from his first classes at the University of Michigan College of Architecture and Design (now the School of Art and Design), where he discovered that not only was art school a lot harder than he’d given it credit for, but it was so much fun that he could hardly be bothered to attend the philosophy and French classes he needed to graduate.

He still wasn’t any closer to being the illustrator we love today, though — instead, his childhood enjoyment of building model cars and boats drew him to sculpture. Bachelor's degree in hand, he headed to the Rhode Island School of Design for his master’s degree and then set up a sculpture studio in Rhode Island. (If you take the jaunt through the selected pieces offered on his site, be sure and click on each of the pictures in order to read their captions — the UFO crashed into a domed building, for example, is funny by itself, but the dry inscription “Event at the Observatory” under it launches it directly into laugh-out-loud territory.)

Van Allsburg only started drawing as a little hobby to pass some time in the evenings, but the works were almost immediately winners. A friend showed them to a curator at The Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, where they were promptly exhibited in 1978. His wife Lisa, a fellow U-M student who went on to teach art in elementary schools, began trying to convince him that his narrative drawing style was well-suited to picture books and took a few drawings to an editor at Houghton Mifflin. The editor agreed and sent a few stories back to Van Allsburg — who thought they were pretty dull. So eventually, he wrote his own.

“I am surprised now that my fairly recent discovery of the illustrated book as a way of expressing ideas did not happen earlier,” he said in his 1982 Caldecott acceptance speech. “The opportunity to create a small world between two pieces of cardboard, where time exists yet stands still, where people talk and I tell them what to say, is exciting and rewarding. … Some people may contend that there is no image more charming that a child holding a puppy or kitten. But for me that’s a distant second. When I see a child clutching a book, especially my book, to his or her tiny bosom, I’m moved. Children can possess a book in a way they can never possess a video game, a TV show or a Darth Vader doll. A book comes alive when they read it. They give it life themselves by understanding it.”

The depth of his commitment to children and reading is revealed almost incidentally in the collection of promotional posters he’s designed. The portfolio includes several years of the Rhode Island Festival of Children’s Books and Authors, the Boston Medical Center Grow Clinic to care for malnourished babies, the American Library Association’s Year of the Young Reader, an inner-city school called Community Prep. Particularly sweet is a poster for the Hamilton School in Providence, an institution dedicated to educating children with disabilities: a kid pries up the cover on a book several times his size, letting loose both a blast of bright light that illuminates his little face and an unruly-looking jumble of letters that tumbles skyward. It captures both the enormous challenge of subduing those letters into neat lines that will transform themselves, silently and almost unbidden, into a narrative — and the vast power that act harnesses.

After winning his next Caldecott, for “The Polar Express” in 1986, Van Allsburg reflected on the relation between the stories we believe and the world we live in. “Lucky are the children who know there is a jolly fat man in a red suit who pilots a flying sleigh. We should envy them. And we should envy the people who are so certain Martians will land in their back yard that they keep a loaded Polaroid camera by the back door. The inclination to believe in the fantastic may strike some as a failure in logic, or gullibility, but it's really a gift. A world that might have Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster is clearly superior to 1 that definitely does not.”

Chris Van Allsburg delivers the Sarah Marwil Lamstein Children's Literature Lecture, presented by the U-M English Department, at 4:30 p.m. on Thursday, April 8 in the University of Michigan Museum of Art's Helmut Stern Auditorium. His books will be on sale at 3:30 p.m. and again at 5:30 p.m., and Van Allsburg will sign copies after the lecture.

Leah DuMouchel is a free-lance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.