The rough side of town: James Thomas Mann's 'Wicked Washtenaw County' explores our sordid past

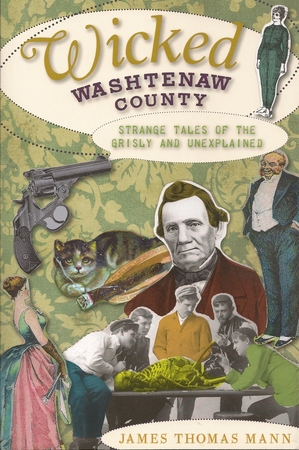

The title of local historian James Thomas Mann’s new book just about says it all: “Wicked Washtenaw County: Strange Tales of the Grisly and Unexplained.” It’s a romp through our criminal record that starts with what may have been the county’s first murder, a case of bullying settled up with gunfire in 1843, and ends in 1926 with “Irene the Bandit Queen,” whose gang of bank robbers lodged at her mother’s Ridgeway farm (and had Mom in cahoots).

In between, there are stops on the Underground Railroad, an exploration of the unsavory methods the University of Michigan was forced to employ in order to teach anatomy, a shoot-out at a “house of ill repute,” pranks gone dreadfully awry and unsolved deaths whose official explanations occasionally tax the limits of credibility. AnnArbor.com chatted with Mann about this walk on the dark side.

Tell me how you came to be a “local historian” — have you always been interested in local history?

First, I was interested in history. And I’m from a family of storytellers, and history provides an unending source of stories. Local history has the added benefit of being able to point and say, “There’s where they found the body.”

How did this particular book come to be?

This is my sixth book. I received an e-mail from an editor of The History Press asking if I wanted to do a book, and after thinking it over for about a 10th of a second, I said "yes." The History Press has a number of different series, and the "Wicked" series is one of them. (The editors) wanted to do something broader than just one city; they wanted it countywide.

Do you have a favorite of the stories in it?

I think the body snatching story (in which the University of Michigan Medical School carried on a standard practice of grave robbing in order to secure cadavers for anatomical dissection) is my personal favorite. I think it’s because of the subject matter, the idea of this prestigious university having to stoop to such a depth to get something they need.

I thought it was interesting that in a way, it’s because the University's medical school was so prestigious that that happened, rather than in spite of it.

They really didn’t have a choice, because they wanted the students to graduate with the best knowledge possible and couldn’t get it any other way. In some places — this isn’t in the book but it probably happened at the University of Michigan too — somebody would come in and say (a medical school) could have the (person's) body for a price, but they wanted advance payment. I don’t think anyone’s been taken up on that.

How did you decide what stories to include?

The body snatching story was one I was familiar with, and I figured that would have the widest interest. And I knew about the deaths under mysterious circumstances of William Benz (who was reported to have committed suicide by hitting himself in the head with a hammer and slicing his own throat before he walked to his woodshed without spilling any blood, stepped over a bloody wheelbarrow, and died) and the woman in Chelsea (named Elizabeth Stapish, who, according to the coroner's jury, "came to her death by strangulation brought about by means of a leather strap around her neck in the hands of some person or persons unknown to the jury"). I also knew about Irene the Bandit Queen. And then I had to go look for other stories.

Tell me about your primary sources — where do you find these gems?

My usual practice is to go through the old newspapers on microfilm and make a copy of anything and everything that looks like it might be interesting, so I had a good place to start. And then I still had some empty spaces to fill, and I had to sit down and find out what I could, so I found myself searching around through my files.

I noticed that you cite newspapers often, and that the names of the local papers changed and combined throughout the book in ways that suggested an interesting corporate history. Have you gotten quite familiar with our local newspaper history as a byproduct of your research?

It is interesting because for many years through the 1800s, if someone was a printer, they printed a newspaper, usually a weekly, and they tended to be pretty partisan. The Ypsilanti Commercial was edited by Charles Patterson, who was a strict prohibitionist. If you could get a prohibitionist angle on a story, he did. He backed a prohibition candidate in 1886 and he lost, and some of the supporters of the opponent decided to give a late night serenade to Patterson. So they got noisemakers and went to his house and made a big racket, and a basement window got broken. Patterson apparently had no sense of humor, and so the next day he sent out over the telegraph a story about how he had to face down this mob who had to come lynch him. By the way, the mob left money behind to pay for the broken window.

What do you think all the changes in the newspaper industry in general mean for historians?

For me, the biggest concern is the lack of multiple sources. It was very nice to have two or three different accounts of the same event, because each one will have details that the others don’t. In the early 20th century, they were much more free with language or would give much more detail of the crime scene, or they would describe a building room by room, giving the dimensions or descriptions.

Do you ever see a current event in the papers and think, “Oh, some 23rd century historian is going to love that?”

I can’t think of any recent stories that would fit into a "Wicked" book. History should be seen through the lens of time. We can’t really judge current events because we’re in them; we need to be able to look back in time and see the effects that something has.

How long do you think it takes for history to “cure”?

I think for the best view of events, 20 years is probably the best. By then, passions have cooled, things have settled down, enough people have died so that you can look at it more clearly for a better understanding of what happened. One thing about selling this book is that one name keeps coming up — I was at the (Ypsilanti) Heritage Festival and this woman came up and said, “Is John Norman Collins in here?” I had to resist the temptation to say he’s still in prison at Marquette, not in the book. But when I said, "No," she tossed it back on the table and walked away. It was 1969-1970 when he was convicted, but he still has a hold on the imagination of people here. His story is one that I’m not sure I want to write about. I know about some of the things he did to his victims.

The stories in this book span from about the mid 1800s to 1926; do you have a favorite period in Ypsilanti’s history?

The 1800s provided a lot of material, as did the early 20th century, and that’s what I’ve been focusing on. Someone once asked about my favorite period of history in general, and I said, ‘from the beginning to the present.’

I have a question about how this work affects what you personally see every day. A number of times in this book, we read something like, “the janitor saw three boys run by but thought nothing of it,” or the like. And it got me thinking about the number of times every day that we see something that doesn’t even make it into our consciousness, or when something’s a little off but we tell ourselves, “It’s probably nothing.” Do you take more careful note of those moments than you otherwise might?

I look around and I notice things more because of this. The other week, I stepped outside and on the next street was this very small girl trying to explain something to two police officers and two ambulance attendants. I had no idea what was going on, and I couldn’t see any damaged car or anything. The police, I know, do not like an audience, so going up and asking what’s going on wouldn’t get the answer I wanted. I found that situation to be rather curious, but I still don’t know what happened.

Do you find the lack of resolution in all of these stories unsettling? How do you feel about that?

It’s the lack of answers that makes them so interesting. But then again, I would like to know what happened, and I think the families would like to have some certainty. None of the families have contacted me to express an opinion, at least so far, which may or may not be good. And the sheriff’s department hasn’t contacted me either, particularly about the unsolved cases. William Benz going 75 yards and committing suicide — my feeling is that the police looked at the situation, thought it was murder, but they couldn’t solve it and decided it was suicide.

Of course they didn’t have the forensics they have today. In many cases, they got a call and just went looking around, and sometimes they got lucky. There was a murder in the 1920s where the entire investigation consisted of driving around, and they did pick up some suspects. They were acquitted, but at least (the police) made an effort.

What’s your next project?

I’m planning to write more books for The History Press. I don’t know what The History Press has planned. (laughs) I figure I could write at least nine more books, and I would settle on any one of them. I’m researching books like "More Wicked Washtenaw," "Wicked Ypsilanti," etc. And I continue this process of looking through old newspapers.

Can we have a sneak peek of what you‘re working on?

There’s Albert Patterson, who disappeared in 1903 and left a note behind saying that when visiting San Antonio, Texas, he stumbled on a meeting of the Mexican mafia and they have been threatening his life. The note was found after he vanished, and I will say that at the time, most people were unconvinced.

The history press has a number of series — there’s "Wicked," a "Haunted" (so I’m looking for ghost stories), chronologies, architecture. So there’s plenty to work with. Washtenaw County has lots of material.

James Thomas Mann will be at Nicola's Books at 7 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 23 to talk about "Wicked Washtenaw County: Strange Tales of the Grisly and Unexplained." You can buy the book at Nicola's, Border's and the Ypsilanti Historical Museum, or order it from The History Press. "And I have copies that I usually carry with me," added Mann, who also contributes a "Historically Speaking" column to AnnArbor.com. "So if you stop me on the street, I'd be happy to oblige."

Leah DuMouchel is a freelance writer who covers books for AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Tom Dodd

Sun, Sep 19, 2010 : 8:40 a.m.

"You can stop me on the street..." There's another fascinating story here, but we won't see it in Mann's books; it's about James Thomas Mann. He is a great success story, himself.

jns131

Wed, Sep 15, 2010 : 10:22 a.m.

He is also coming to the YDL in 2 weeks. Can't wait to meet and greet this author. Thanks for the article.