Ann Arbor's Mark Creekmore focuses on 'story' of mental illness

“Society will be better off with people with mental illness participating in as many ways as they possibly can.”

That’s what Mark Creekmore believes.

Mark, 65, of Ann Arbor, holds a doctorate in sociology and social work from the University of Michigan. He’s a busy man as a lecturer at U-M and as executive director of Community Service Systems Inc., a private, nonprofit agency that helps organizations develop ways to meet their missions. But he still finds time -- a lot of time, actually -- to volunteer.

He’s on the board of the Washtenaw Community Health Organization, which funds mental health services in four counties. He’s also on the board of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) for Washtenaw County, chairs the policy committee of NAMI Michigan and is helping lead a NAMI project entitled “Telling Your Story.”

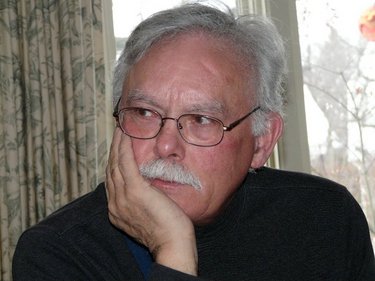

MARK CREEKMORE: The Ann Arbor resident is helping lead project entitled “Telling Your Story” about mental illness.

Courtesy photo

Mark is particularly concerned about people with mental illness in jails and prisons. He says at least 20 percent of all prisoners are seriously mentally ill, making the criminal justice system “the largest institutional provider of mental health services in the world.”

It’s expensive -- Michigan spends more on prisons than on higher education -- and can be deadly. One prominent example is the case of Timothy Souders, whose death due to dehydration in a Jackson, Mich., prison was featured on “60 Minutes.”

Mark, who has served as an expert witness for prisoners in federal district court, declares unequivocally: “The Department of Corrections is not a responsive bureaucracy.” He has been active in Crisis Intervention Teams, which bring “people with mental illness, their families and caregivers, mental health professionals and police together to develop strategies for de-escalating crises and avoiding unnecessary arrests and imprisonments.”

Mark’s goal is to keep as many mentally ill people out of prison as possible. That would relieve the prison overcrowding problem overnight, he maintains.

Before the late ’70s and early ’80s, people with developmental disabilities and mental illness were often institutionalized for life. Gradually those large state institutions were closed and small group homes were opened, as society embraced the idea of providing the least restrictive treatment possible. During part of that transition, Mark was executive vice president for Spectrum Human Services, which opened some of those group homes.

“Because people with mental illnesses and people with developmental disabilities both have chronic and profound disabilities, and despite the fact that many suffer from both developmental disabilities and mental illness, they are perceived differently and treated differently,” Mark says.

Part of the reason is that people with mental illness have a hard time retaining the social support of friends and family.

Mark says many people with mental illness got “derailed” from previously successful lives. They can be successful again, he says, but only if society makes accommodations and finds ways to tap their talents.

Mark is interested in society’s safety nets because he grew up in a time without them.

And he could have used one.

Both his parents were orphaned by age 16, and “they were scarred,” Mark said. “I grew up in the aftermath of two people whose childhood had been squandered.” Neither his father, an electrical engineer, nor his mother, a public school Latin teacher, were social people.

In fact, they lived on six acres outside Oklahoma City in a home Mark’s father designed, “creating their own reality” where they were involved in as few “social institutions” as possible, Mark said.

He was taught to be private: “I was told never to talk about what happens at home, at school. … I thought there’s got to be a better way. That’s why I’m in social work.”

He left Oklahoma to attend Williams College in Massachusetts, majoring in political science, before he attended graduate school at U-M.

After earning his Ph.D. he took a job for two years managing the Ann Arbor Cooperative Society, a venture where consumers combined their buying power. That led to Spectrum and, in 1990, he founded Community Service Systems Inc. and began teaching at U-M in the School of Social Work and the Department of Psychology.

He believes the U.S. is now at another unique moment in time, much like the transition away from institutionalization. This time, it’s related to health insurance. “The people who really need medical insurance can’t afford it,” he said. “We’re spending too much for too little care. We need to get a handle on it … realize there’s no easy solution.”

In his effort to get people to stop fearing mental illness, Mark tells people to take stock of how it has affected their family -- almost everyone can come up with examples. He encourages Ann Arborites to talk to the homeless people selling newspapers on the street corner and volunteer with local agencies. And he urges everyone to invite a NAMI spokesperson to their social group or civic club.

People with mental illness won’t go away, Mark says.

“They want and deserve independence, and want to be valued in the community.”

Kyle Poplin is publisher of The Ann magazine, which is inserted monthly in various print editions of AnnArbor.com. He’s also searching, through this column, for the most interesting person in Ann Arbor. If you have anyone in mind, email your idea to theannmag@gmail.com.

Comments

Khurum

Sun, Nov 6, 2011 : 6:14 p.m.

I have worked with Mark in my previous life as a police officer and his dedication and insight was invaluable. Thank you for highlighting his work.

blueeyedpupil

Sun, Nov 6, 2011 : 2:58 p.m.

Mark, you are an amazing man. You have dedicated your life to helping those of us with mental illness live a full life. Helping us tell our stories of mental illness, so that others will understand that its not something to be afraid of. We are just people like everyone else. We just carry an extra burden. Society is slowly beginning to accept us as the people we are, and understanding that we do not need to be locked away from society. But we still have a long way to go. With your help we will overcome the stigma and fear. Your advocacy for full and needed benefits for the mentally ill is such a necessary action. No one should be homeless due to mental illness. No one should be untreated for mental illness in prison. We all deserve to live a full and successful life. We now are up against the state making cuts to services due to budget cuts. That the state has made no allowance in the new rules, for mental illness, but only for physical disability is unconcionable. Many of us live at the poverty level and to lose benefits will only plunge us further into the abyss. Keep working for our rights and keep helping us tell society that we are just people like anyone else. Continue to help us work for a fair deal from the government, that allows us to live with dignity and hope.

Lolly

Sun, Nov 6, 2011 : 11:57 a.m.

Thank you, Mark, for your work and your caring; it is inspiring. We need more people like you working for the overlooked in our society.

Goofus

Sun, Nov 6, 2011 : 9:15 a.m.

People with mental illness are just everyday people with an extra burden. There's nothing strange or difficult about them being admitted to society unless society makes it so.

JustMyOpinion

Sun, Nov 6, 2011 : 12:04 a.m.

I wish him every success. It's a difficult proposition to integrate folks with various special needs into society at large. It requires a great deal from the rest of us in terms of tolerance, patience and a willingness to slow it all down and not be hasty. Its hard to be isolated as a person with any developmental issues or mental illness, but it can be worse to be humiliated or dismissed. I think to be successful, such programs should begin in schools.