Deaf man fights the odds to become University of Michigan physician

When doctors deliver babies, most of them can hear the first life-affirming cries of the infants as they enter the world.

Dr. Philip Zazove can't.

In 1981, Dr. Philip Zazove became the third certified deaf physician in the history of the United States. Now a specialist in family medicine at the University of Michigan Hospital, he has spent more than 30 years in the medical field.

When asked why he chose medicine, Zazove replied, "I like to help people. I like medicine. I like relationships with people."

But obtaining his dream job was no easy task.

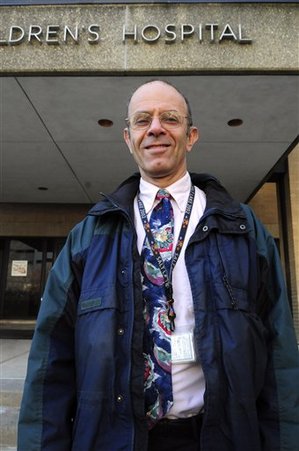

Dr. Philip Zazove poses in front of the University Michigan Children's Hospital in Ann Arbor. In 1981, Zazove became the third certified deaf physician in the history of the United States. Now a specialist in family medicine at the University Hospital, he has spent more than 30 years in the medical field.

AP Photo/The Michigan Daily, Jed Moch

Now 58, Zazove was diagnosed with profound hearing loss at age four. Though Zazove can't pinpoint the exact moment he lost his hearing, he recalls the frustration he felt when he couldn't hear what his father was saying as he helped him organize books on a shelf one day.

"I said, 'Daddy, you have to turn around so I can see you, so I can understand you,' " Zazove recalls. Zazove could only understand his father by reading his lips, a task that could not be achieved when his father's back was turned to him.

The Zazoves recognized something was wrong with their son and took him to doctors who evaluated him and diagnosed his deafness.

"They said I had a profound loss, and I would never be educatable," Zazove said. "And I should go to a deaf school, and I would be lucky if I got a job as a janitor."

But because Zazove had already learned to speak English before losing his hearing, his situation differed from children born deaf who have never learned to speak.

Rather than placing him in a school for the deaf, the Zazoves decided to "mainstream" their son and educate him in public schools. Zazove says he was the first deaf child to be mainstreamed in the northern Chicago suburbs.

But school administrators met this decision with opposition. Every year, Zazove's teachers would try to convince his parents to send him to a deaf school.

"Even though I did very well the year before, the teacher would say, 'A deaf child? I can't have one of those,'" Zazove said.

According to Zazove, the majority of deaf people cannot read above a sixth grade level, while only 13 percent graduate from college.

Yet, Zazove defied the odds and attended Northwestern University in 1969.

When it came time to apply for medical school, Zazove remained optimistic.

But despite stellar grades, high medical board scores and gushing recommendations, all 18 medical schools he applied to denied him acceptance.

While none of the letters openly stated the school would not accept him because of his deafness, Zazove knew that was the underlying reason.

Despite the setbacks, he didn't allow his disability to stop him.

Zazove put off medical school and remained at Northwestern to obtain his master's degree. When his program was finished he decided to give medical school another shot, and this time applied to nearly 30 schools.

During the application process, a second-year medical student at Rutgers University — one of the schools Zazove applied to — heard about Zazove. The student himself had a profound hearing loss and decided to help by setting up an interview with representatives from Rutgers.

Today, Zazove doesn't know if that made a difference, but Rutgers was the only school to accept him.

After two years at Rutgers, Zazove transferred to Washington University in St. Louis where he met his wife, Barb Reed, who was studying pediatrics at the time. She is now a physician in the Department of Family Medicine in the University of Michigan Health System.

Reed emphasized what an "excellent" father her husband is and that his hearing loss never stopped him from caring for his daughters Katie, now 26, and Rebecca, 28.

The family came to Michigan in 1989. Both Reed and Zazove got jobs at UMHS in the Department of Family Medicine, making Zazove the first deaf physician to work in the state of Michigan.

As is the nature of family medicine, Zazove forms close relationships with his patients and their families.

"The thing about family medicine is taking care of family, continuity of care and prevention and keeping people from getting sick," Zazove said.

Zazove cares for about 2,500 patients at the hospital, of which roughly 10 percent have a hearing loss. Because Zazove can communicate in sign language, some deaf patients drive hours to see him.

However, the average deaf person earns $25,000 or less annually, and Zazove says many can't afford to see doctors.

"Some of them get Medicaid," he said. "But because of the economy, every state is trying to cut back."

Zazove admits he's not sure how many of his hearing patients realize he's deaf. Some think he has an accent, on account of his muffled speech, and ask if he's Italian because of his last name.

"Sometimes they say 'What country are you from?' and I say 'From Chicago,' " Zazove said.

Two and a half years ago, Zazove received a cochlear implant — a surgically implanted device in the ear that helps pick up sound. Since the implant, Zazove said more of his patients are making the connection that he's deaf.

Though the device is supposed to improve hearing, Zazove said his doesn't work very well. A year and half ago, he got a second implant which has slightly improved his hearing.

"It works better, and it's only getting better, but it's not what I had hoped," he said.

Instead, Zazove relies heavily on lip reading to converse with his patients and others in his life. He said people who lip read can only understand about 20 percent of what someone is saying, and must rely on context to fill in the rest.

"I know we're talking about me, my life," he said of our conversation at an interview last month. "If we were talking about Dick Cheney paying his rent, and you didn't tell me that, I'd probably have no idea. It would take me a while to figure that out."

Zazove noted that lip reading comes in handy when communicating with patients who have lost their voice from being sick or after coming out of surgery. "I can read their lips, and other people can't understand them," he said.

While lip reading may help him communicate with patients, it becomes a problem during surgery when doctors wear surgical masks.

"It's hard," he said. "People are talking, and you have no idea what they're saying."

Zazove admitted this was an issue while learning how to perform surgeries in medical school. To make up for the lack of auditory learning, he would have to ask many questions and pay extra attention.

Today, Zazove is working with the Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses to develop a clear mask that allows deaf doctors and patients to read lips.

The mask is just starting to be adapted by professionals in the medical field, and Zazove said it will make work easier for future generations of deaf physicians.

Besides not being able to communicate during surgeries, Zazove said many deaf physicians — of which there are now more than 100 in the country — have trouble using stethoscopes to listen to heart rates.

Zazove can hear through a stethoscope, but other deaf doctors use amplified or visual stethoscopes. One veterinarian Zazove knows has learned to read heart beats by touching her hand to an animal's heart.

"She can tell if it's a murmur or anything because she's developed the ability to do that," he said. "It's amazing, it really is, what people can do."

Despite his hearing loss, Zazove said patients rarely express concern about his diagnoses.

"Most people figure if you're an M.D. and you went through med school and residency and are certified, you know what you're doing," he said.

In some cases, his deafness helps establish better relationships with his patients. Zazove said he thinks his disability may inadvertently lead him to providing better patient care.

"I would be willing to bet as a general rule that deaf physicians are much more attentive to their patients. They have to be to focus," he said. "People tell me that all the time, 'I love the way you look at me and listen to me.' "

Joyce Kaferle, the medical director in the Department of Family Medicine, has worked with Zazove since the early 1990s. She said she has found his hearing loss helps him better connect with patients.

"I think that it's really an invaluable thing for his deaf patients because he understands what they're going through a lot more than other people do," Kaferle said.

However, Kaferle said Zazove's patient care time has become limited due to the amount of administrative work he has taken on.

Zazove is one of 25 professionals in the country who conduct research on how hearing loss impacts health. Results from Zazove's studies may be used in the future to help the deaf have a better quality of life.

Through his research, Zazove discovered people with even a slight hearing loss tend to have poorer health. He has yet to determine why, but he attributes the discovery to the fact that hearing doctors treat patients with hearing loss differently.

In 1994, Zazove published an autobiography "When the Phone Rings, My Bed Shakes." His second book, out in March, is titled "Four Days in Michigan." While the book is classified as fiction, the story describes the differences between people in the "deaf" and "Deaf" communities.

Zazove explained that people born with a profound hearing loss are considered "deaf" — lower-case "d'' — and often keep quiet about their disability, while people in the "Deaf" community — upper-case "D'' — communicate by sign language and embrace their hearing loss. According to Zazove, the "Deaf" community views him as "deaf" because he can hear slightly.

"From a Deaf person's perspective, normal is deaf. Abnormal is hearing," Zazove said.

This is also the group that makes less than $25,000 per year. For that reason, Zazove said few people in the Deaf community live in Ann Arbor because the cost of living in the city is too high.

"They can't afford to live here. It's too expensive," Zazove said. "Most of them live in Flint, or Detroit, or Grand Rapids or small towns where it's cheap. I would say there's probably 30 or 50 people in the Deaf community in Washtenaw County here for that reason."

As far as students, Zazove said there may be a total of three to 15 students with a hearing loss who attend the University every year. The Office for Students with Disabilities helps them as much as possible by providing interpreters to take notes during classes and translate lectures.

Though this may make a difference in deaf students' educational experiences, they still face challenges outside the classroom. Zazove explained how being deaf is a difficult disability to have because it's not visible.

Using a hypothetical situation, he said if students are at party and a blind student walked in, most people would go over and help him or her. But if it was the same party and a deaf student walked in, no one would know the student was deaf and no one would offer assistance.

Zazove says scenarios like this have happened often in his career. He mentioned one instance recently where, after leading a medical conference, a man wearing a surgical mask due to illness approached Zazove.

"He came up to me said 'You did a good job moving this along' and left," Zazove said. "I had no idea what he said. Somebody who knew me said, 'I bet you didn't understand him,' I said no, and he told me what (the man had) said."

From these experiences, Zazove understands why some people keep quiet about their deafness.

"I think that's why people with hearing loss would finally give up and say I don't want anybody to know, it's too much trouble, it doesn't change anything anyway," he said.

Yet, despite the myriad bumps and setbacks, Zazove has learned to live with his disability and embrace life regardless of his existence in a silent world. Reed said her husband's deafness is a characteristic that makes him so special.

"He's a very beloved physician," Reed noted. "He has a loyal patient clientele who stick with him year in and year out. So while I do think it was difficult for him to become a physician, he's a great example that deaf individuals can do all kinds of professional jobs very well."

Comments

Rishi

Mon, Jul 5, 2010 : 10:43 a.m.

I know another deaf physician and she has been using a visual display on a stethoscope to 'listen'. Its something for the iPhone, not surprisingly. And to interpret the display, www.easyauscultation.com has a library of waveforms.

Tom Willard

Tue, Mar 23, 2010 : 12:05 p.m.

Wow, what a chilling sentence: "Dr. Philip Zazove can't." The article tells of what he can and does do while the writer chooses to emphasize what he can't do. It is a shame that hearing reporters always do this when they write about deaf people. "So-and-so can't hear the applause etc etc..." Yuck!

jinxx

Mon, Mar 22, 2010 : 6:22 p.m.

It's because of stories like this that I love AnnArbor.com. I didn't know that such an amazing person lived in our community! :] Thank you, AnnArbor.com!

Ann English

Mon, Mar 22, 2010 : 6:07 p.m.

When Dr. Zazove first came to a doctor's office with two others almost twenty years ago, I was told that he specialized in bones and joints. So I first went to him with a bone complaint. With each appointment with him, I got used to his fast speech. I did read his autobiography, borrowing it from a hard-of-hearing friend, who wanted me to review it for her.

seldon

Mon, Mar 22, 2010 : 8:57 a.m.

I've met Dr. Zazove several times (not as a patient), and am one of the people who didn't realize he was deaf until someone told me.

Anonymous Due to Bigotry

Mon, Mar 22, 2010 : 5:43 a.m.

These days, there should be no reason why being deaf should prevent anyone from doing anything.

Al Feldt

Sun, Mar 21, 2010 : 10:30 p.m.

As a late deafened adult, I am another of Phil Zazove's many friends and fans. He is an inspiration himself and the Zazove Foundation helps many promising deaf college students.

Joan(joni) Smith

Sun, Mar 21, 2010 : 7:15 p.m.

When Dr. Zazove came to Michigan 20 years ago, I made an appointment because I had to check him out before recommending him. I served as the Coord. of Svcs. for Deaf/HoH students at UoM and had to make sure. Wow, he is super and is still my personal physician. He served on the Board of Directors for the Center for Independent LIving for many years, served as the Camp Physician for UofM's Shady Trails Camp in Northport for years and serves on the Board for AnnArbor's Women's Safe House. His family scholarship provides funding for higher education for Deaf students every year. He ran for political office in the past and many are encouraging him to do it again. He is a community hero.

Patti Smith

Sun, Mar 21, 2010 : 6:44 p.m.

Awesome story! I am a special ed teacher and I deal with mainstreaming (now called "inclusion") on a daily basis. My Facebook friends know the daily struggles I go through, trying to get my students where they belong--with their peers and with access to the general ed curriculum. Bravo to Dr. Zazove and his parents for having the foresight--and fortitude--to do what was right.

Elizabeth Donnelly

Sun, Mar 21, 2010 : 5:15 p.m.

I have been treated by Dr. Zazove many times at his clinic and I have always found him to be extremely knowlegable, efficient, capable and extremely kind. He is a fantastic physician!