In Ypsilanti, a Buffalo Soldier tells tales of courage, history

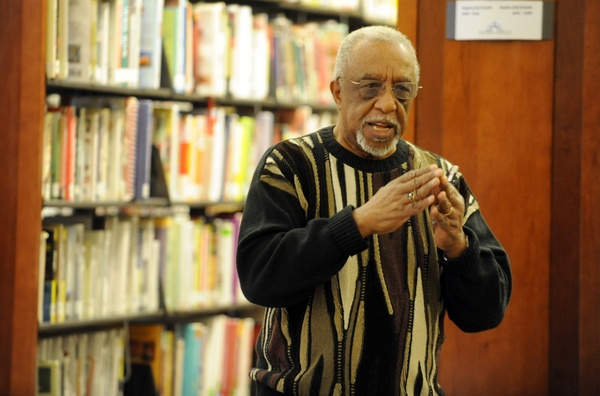

Jim Mays, 74, never served in the military but has been telling the stories of the Buffalo Soldiers for more than a decade, as he did recently at the Ypsilanti District Library for Black History Month. The Buffalo Soldiers were the first black fighters to be allowed to serve in the U.S. Army in peacetime.

Melanie Maxwell | AnnArbor.com

Editor's note: This story contains the usage of racially offensive language as part of a quote from the subject of this story, who used it to make a point about racism and epithets.

It was early in the lecture for questions, but the dreadlocked young man was insistent that Jim Mays hear him out.

"Can you validate something for me?" he asked.

"I can try," Mays said.

Mays was giving a lecture at the Ypsilanti District Library last week on the Buffalo Soldiers, the black fighting units that served from 1866, when blacks were admitted to the U.S. Army for the first time during peacetime, to 1948, when President Harry Truman integrated the military, and the young man objected to Mays' use of the word black.

"What's this word 'black' you keep using?" Dreadlocks pressed him, his female friend nodding vigorously, smiling approvingly. "Tell me the origin of this word. Where did this come from, to call someone a black person?"

"In the 1860s, black people trying to serve their country were called by any number of names," Mays responded, taking a step in his questioner's direction. "Black was one of them, Negro was another, as was colored. Another was nigger."

That settled, Mays, 74, could regain the room's attention. Dreadlocks was gone 20 minutes into the 90-minute lecture.

The 1866 law allowing blacks to serve in peacetime came with special stipulations. Black units fighting could serve only west of the Mississippi River and only in limited numbers. The black units were also made to assist in the government's push to move Native Americans west.

It is in fighting the government's Indian War that the black fighters were given the "Buffalo Soldier" moniker, a measure of respect for their fighting prowess, which recalled memories of the feared buffalo. At the library lecture, Mays regaled his listeners with tales from the distant and not-so-distant past.

Cathy Williams didn't regard as legitimate the military’s stance that only men could fight on the front lines of the Indian Wars, so she joined up to help, enlisting as William Cathey, a man.

Nothing about Williams' appearance indicated she was a woman. Indeed, she was given to walking into saloons, challenging the biggest guy there, and knocking him out cold in her pre-Army days.

Her size, combined with the times — in the 1860s it was not common for men to undress around each other, let alone shower near one another, Mays said — allowed Williams to maintain the ruse for a few years.

Then, one day, William Cathey caught a bullet to the thigh.

After being transported back to the field hospital unit, Mr. Cathey's pants were cut off, revealing "him" to be Ms. Williams. She was discharged immediately and it was because of Williams' cunning, Mays said, that the Army instituted the "short arm inspection," to verify that its men and women are who they claim to be, at least from a gender standpoint.

Today Williams is celebrated as the first female Buffalo Soldier, and she wasn't the last of her kind.

A poster shows the Buffalo Soldiers and the motto "Ready and Forward."

Melanie Maxwell | AnnArbor.com

The Texas communities near Camp Hood "were replete with hard-cord racists eager to administer lessons to unwary black soldiers who might think present military status transcended time-honored racial etiquette," wrote historian and archivist John Vernon, who studied the young man's court martial decades later.

The 25-year-old officer was sitting on a Southwestern Bus Company vehicle, exactly a month after D-Day, when driver Milton Reneger ordered him to move to the back. He refused and the commotion grew larger as police, military police and townspeople all arrived at the scene. By the end of it, Vernon writes, the young man was hit with a general court-martial for "a number of monstrously serious transgressions — including the show of disrespect toward a superior officer."

But Jackie Robinson was meant to make history, not be a statistic. Captain William A. Cline, a white Army-appointed defender, represented Robinson, and was able to introduce doubt as to whether Robinson had ever been given official orders to stand down. The court-martial was dropped.

Afterward, Robinson chose to leave the Army.

He would resurface in the national consciousness in 1947 when, with the help of University of Michigan Law School graduate and Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, he broke Major League Baseball's color barrier, a plan he and Rickey set in motion in 1945.

Robinson was named baseball's first ever Rookie of the Year after the '47 season. By 1949, Robinson won Most Valuable Player accolades in the National League, another first for a black player. Robinson's No. 42 is the only number retired across all of Major League Baseball, the only jersey in America's four major sports retired leaguewide. A number of times last decade, baseball allowed players to honor Robinson by wearing No. 42 on April 15, which is Jackie Robinson Day.

Up to then, the stories had been received like so much esoterica, interesting trivia, perhaps, when watching "Jeopardy!," but the Jackie Robinson story made the dozen or so audience members sit straighter in their chairs.

Mays' point, that the service of Buffalo Soldiers weren't merely the details of black history, but rather the fabric of American history, was made.

For the purpose of balance, Mays also talked about black cowboys from the Western frontier, "scoundrels" like Nat Love, also known as Deadwood Dick, and Ben Hodges, who were as feared and cruel as the Jesse Jameses and Butch Cassidys we celebrate today.

Stephanie Browne, who brought her daughter Imani Wells along for Mays' presentation, was surprised to hear that Robinson was fighting racism long before 1947.

"I didn't know that Jackie Robinson was almost kicked out of the military for speaking his mind," Browne said. "And I definitely hadn't heard about Cathy Williams — it's good to see that us women were represented even then."

Browne brought the 7th-grader along as part of their effort to embrace Black History Month this year.

"You look too young to have been a Buffalo Soldier," someone in the crowd said to Mays.

He is.

The Buffalo Soldiers disbanded after President Truman's Executive Order No. 9981 of July 1948, which integrated the military. Few World War II veterans exist these days, and even fewer Buffalo Soldiers. Their memory lives on through historical groups like the now-defunct Washtenaw County Buffalo Soldiers, which Mays joined in 1995.

Mays, who turns 75 this year, was too young to serve in World War II and his hips were too fragile from high school football for him to participate in Vietnam. He never did serve in the military. Mays stumbled upon the Washtenaw County Buffalo Soldiers after retiring from Ford Motor Co. after 30 years in production.

He was looking for a way to connect with his history, black history, and found a group of black men who were riding horses and doing re-enactments and trading war stories on the exploits of the Buffalo Soldiers.

He was hooked. Soon he bought a horse, then another, which he would ride when meeting up with fellow "soldiers" or on Memorial Day or the Fourth of July or at the Ypsilanti Heritage Festival.

The local group's heyday was from about 1992 to 2007. But as the economy soured, it became too expensive for many of the guys to continue maintaining their horses, which between pills and vet visits and transport can cost up to $4,000 a year.

The last stand of the Washtenaw County Buffalo Soldiers, Mays recalled, was at the 2007 Ypsilanti Heritage Festival.

Not only does each horseman need his own horse, but he also needs a trailer and a truck to transport it. Ideally everyone would have their own transportation, but in reality one guy usually has the trailer and the pickup. That guy was Mays.

That festival morning in 2007, Mays woke up early and left his home in Ann Arbor in order to pick up his horses in Chelsea and drop them off in Ypsilanti. As someone watched the horses, he grabbed another member's horse in Belleville or Carleton, then dropped it off, then went back to pick up more. By the end of the festival, he had seen about enough of the horses, and in the years since, the economy has made horse ownership too expensive for most of the Buffalo Soldiers.

Had Mays' lecture been given a decade ago, he would've been surrounded by fellow "soldiers," all decked out in era-appropriate garb, each talking about his or her favorite Buffalo Soldier. Those were the days.

Today, Mays and "two or three old friends" are the last remaining vestiges of the Washtenaw County Buffalo Soldiers. The group's former website, wcbs.org, now belongs to the Western Conference on British Studies. It lives on only when Mays lectures on the Buffalo Soldiers.

"As the economy headed south," Mays laments, his hands pantomiming a rock falling off a cliff, "we went right down with it."

James David Dickson can be reached at JamesDickson@AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Cheryl

Tue, Mar 1, 2011 : 10:39 p.m.

I am a little confused about and definitely saddened by the role the Buffalo Soldiers played in oppressing and massacring Native Americans. The angry, disrespectful young man embodies my experience of people who refuse to hear anything but their own anger. I do hope that as the economy improves; the active reenactors will return. Thank you Mr. Mays for presenting and helping to keep this interest alive. "As long as the story is told....."

Patrick Hunt

Mon, Feb 28, 2011 : 1 p.m.

I lived next door to a Buffalo Soldier for 10 years in Washington DC. He often spoke of his time in Europe during World War II. What struck me most about his stories was his grace and acceptance of a situation that was so unjust. Fifty years after his service he still referred to his white officers with a respect that was never accorded the black soldiers. As a white man who came of age during the civil rights movement, I found his sense of self and strength of character very admirable. At his funeral there was a wonderful picture of Billy as a young soldier proudly wearing the Buffalo insignia on his army uniform. The work that Mr. Mays is doing should be supported.

Erich Hicks

Sun, Feb 27, 2011 : 8:38 p.m.

There are thousands of untold told stories, and many twisted ones. Keep telling that true history: Read the greatest fictionalized 'historical novel', Rescue at Pine Ridge, the first generation of Buffalo Soldiers. The website is: <a href="http://www.rescueatpineridge.com" rel='nofollow'>http://www.rescueatpineridge.com</a> The greatest story of Black Military History...5 stars Amazon, and Barnes & Noble. Youtube commercial: <a href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iD66NUKmZPs" rel='nofollow'>http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iD66NUKmZPs</a> Rescue at Pine Ridge is the story of the rescue of the famed 7th Cavalry by the 9th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers. The 7th Cavalry was entrapped again, after the Little Big Horn Massacre, fourteen years later, the day after the Wounded Knee Massacre. If it wasn't for the 9th Buffalo Soldiers, there would of been a second massacre of the 7th Cavalry. This story is about, brutality, compassion, reprisal, bravery, heroism and gallantry. Visit our Alpha Wolf Production website at: <a href="http://www.alphawolfprods.com" rel='nofollow'>http://www.alphawolfprods.com</a> and see our other productions, like Stagecoach Mary, the first Black Woman to deliver mail for the US Postal System in Montana, in the 1890's, spread the word. Peace.

John B.

Sun, Feb 27, 2011 : 8:03 p.m.

Thank you, James! Another excellent article.

Ricki

Sun, Feb 27, 2011 : 6:50 p.m.

More info: <a href="http://www.buffalosoldierstribute.com" rel='nofollow'>www.buffalosoldierstribute.com</a>

Ricki

Sun, Feb 27, 2011 : 6:45 p.m.

Did a little Goggling, there is a documentary called : The Invisible Men of Honor The Legend Of The Buffalo Soldiers