Dominique White raising two teenagers after long journey to becoming an Eastern Michigan tailback

Eastern Michigan walk-on running back Dominique White (left) has managed to be the Eagles' third-leading rusher while raising two teenagers.

AnnArbor.com file photo

Three years, nine months and two weeks. That’s 1,386 days. In college football terms, 37 regular season games. That’s how long Eastern Michigan junior running back Dominique White waited. From the last carry of his high school career, to his first collegiate one.

On Saturday, Sept. 10, Week 2 against Alabama State, White entered the game late in the fourth quarter for injured teammate Dominique Sherrer. Wearing the number 38 -- in the 38th game since he’d last touched a football -- White finally got that first carry.

The 5-yard gain was White’s only carry of the game and inconsequential in the 14-7 win. What has followed has been anything but. White has led the 6-5 Eagles in yards (574), tied for the most touchdowns (5) and had the second-most carries (118) in the nine games since.

White’s ability to handle the increased workload may come as a surprise to the casual observer, but not to those who know him. His increased responsibility on the field pales to those he’s handled away from it.

Last spring, White became the legal guardian for his two teenage brothers, Blaine and Jaishon Ellington.

Cooking, cleaning, making sure Blaine, 13, and Jaishon, 16, are fed and on their way to school on time. That’s the hard part of his day. Praising them for a job well done and disciplining them when needed. That’s the tough part.

Taking some extra hits on a Saturday? A relative cakewalk.

EMU FOOTBALL

WHEN: 11 a.m., Friday.

WHERE: Huskie Stadium, DeKalb, Ill.

TV/RADIO: ESPNU/WEMU (89.1 FM)

ODDS: Northern Illinois is favored by 19.5 points

Saturday, Oct. 1, Week 5 against Akron. With Sherrer still injured, White has become a more consistent part of the Eagles rushing attack. He runs for 164 yards and three touchdowns on 28 carries in the 31-23 win.

The numbers weren’t just career highs in all three categories for White. They more than doubled his combined career totals.

It was a benchmark day for Eastern, too. The Eagles eclipsed their win total from the first two seasons of the Ron English era.

White quietly answered questions at the postgame press conference, showered and went home. He didn't celebrate with teammates, despite the fact that he would surely hold Big Man on Campus status for the night.

White needed to get home.

Jaishon, a senior at Huron High School, needed a ride to his last homecoming dance, so White dropped him off. Blaine, a freshman at Huron, was caught cheating on an assignment in school, so White forbade him from going to the dance. White stayed home with him.

White felt slightly guilty about the latter, but quickly got over it.

“If (Blaine) messed up one time (and wasn’t punished), he probably would have kept doing it over and over again,” White says. “He’s got three more (homecoming dances). He’ll be alright.”

Dropping off one brother at the dance and following through on a punishment for the other. It was a career night for him as a guardian, too.

Dominique White and his mother, Clara "Mae" Ellington, in 2005. Ellington died that April of breast cancer.

Mae started as a foster mother for Jaishon and Blaine in 1997, when Blaine was just months old, and eventually legally adopted them. She raised the two along with Dominique in her Rosedale Park home on Detroit’s upper west side.

“When you walked in her door, you could tell there was a sense of love. She was a model parent,” says Cynthia Bell, a former licensing supervisor for the Ennis Center.

It was Bell who first visited Mae’s home to ensure it was suitable for raising children, and she, a suitable foster mother, as is procedure.

Bell says on such home visits, where children are already present in the home, she would try to gauge how the introduction of more children would affect the environment.

“There was no competition, as there often is in those situations,” Bell recalls. “(Dominique) knew he had a place in his mom’s heart that was not to be challenged. There was a special place in Mae’s heart for everybody.”

Both Blaine and Jaishon without hesitation refer to Mae as “Mom” and to White as their brother.

Blood may be thicker than water, but some bonds are thicker still.

“She always cared for us like we were her own,” Jaishon recalls.

Were it not for White’s strong resemblance to Mae, no one could have guessed which of the boys were adopted.

“It was never unequal, with anything," Blaine says. "Not one time.”

Mae’s doors were open to everyone. Kason Dickerson, a defensive back at Eastern Michigan and White’s cousin, fondly recalls spending most weekends of his childhood at her house. He refers to Mae as his “second mom.”

Her Halloween parties were legendary. Christmas, Thanksgiving, Fourth of July, Mae was always the host.

“She’s a beautiful person, man,” Dickerson says. “She’s like, the angel.”

While Mae’s time on earth is remembered as a blessed one, it was also far too short. Breast cancer took her life in April of 2005 at the age of 52.

At her memorial service, an obituary tribute to Mae was entitled “A Lady With So Many Umbrellas.”

“Mae was known to invite stranded motorists, tired women with children at bus stops and anyone who appeared to be in distress under her unselfish umbrella of compassion,” the tribute read.

White’s older sister, Michelle Wheeler, 42, had moved back home to help Mae through her chemotherapy. When Mae died, Wheeler became the legal guardian for Dominique, then a freshman in high school, and Blaine and Jaishon, both in elementary school.

Strong male role models

White’s father, Calvin White, died when Dominique was 7. Suffering from complications from a blood clot, he died in his sleep at the age of 38. The same number Dominique wears for Eastern on Saturdays.

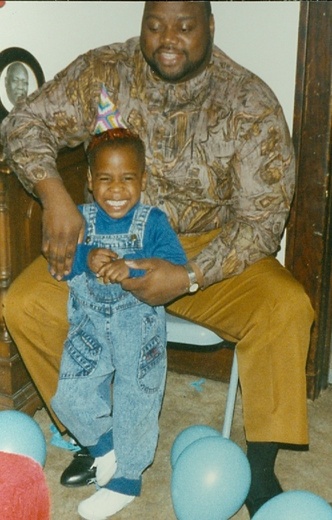

A 3-year-old Dominique White with his father, Calvin White, in 1993.

After Calvin died, Mae kept Dominique steeped in activity.

Before his freshman year of high school, White had asked his mother to send him to Orchard Lake St. Mary’s, an all-boys private Catholic boarding school 45 minutes away from Detroit. Wheeler and Mae agreed boarding school might be the best thing for Dominique as Mae’s condition worsened.

“We thought it would be very good to go there,” Wheeler says. “He didn’t have to watch her suffer.”

Mae had taken early retirement from a job with the City of Detroit and from a job with the Detroit Institute of Art when she became sick. Combined with social security and death benefits through her insurance, tuition at St. Mary’s wasn’t a problem when White was in high school. Blaine and Jaishon attended private school closer to home.

It was at St. Mary’s that White contends he grew from a boy to a man. Or as he puts it, into a “St. Mary’s man.”

But it wasn’t always easy becoming a St. Mary’s man. Richard Rychcik, Dean of Discipline at the school, recalls the time around his mother’s death as a tough one for White.

Rychcik took White under his wing and drove to the hospital with him when Mae was in her final stages of life.

Along with his father, White lists Rychcik and his coach at St. Mary’s, George Porritt, as the strong male role models in his life.

It was something he sensed his brothers were lacking.

“Going to Orchard Lake, I learned stuff from the men that were there,” White says. “So I put it in my own hands, asked my sister if I could take full guardianship of them.”

Wheeler was hesitant. It wasn’t a monetary issue. Death benefits for Blaine and Jaishon continue until their 18th birthdays, and adoption subsidies from the state cover health insurance.

But White was just a college kid? How could he handle such a responsibility?

The road less traveled

Sherrer is now back from injury, but because of White’s production, he’s still a fixture in the Eagles offense.

Sherrer, White, Javonti Green and dual-threat quarterback Alex Gillett lead a four-man rushing attack averaging 226.09 yards a game on the ground, 13th in the nation, and third in the MAC.

Of his rise up the depth chart contributing to Eastern’s success, White shrugs his shoulders and quietly, but confidently, states, “God works in mysterious ways.”

White graduated from St. Mary’s in 2008 with scholarship offers from Indiana State and Grand Valley State, while larger programs such as Clemson and Connecticut had shown interest.

But White was red-flagged by the NCAA after he had a significant jump in his ACT score the second time he took the test. White maintains the jump was due to him studying like crazy before the second test, compared to not at all the first time he took it.

In the end it didn’t really matter. The offers were pulled and the interest dried up. He didn't have the grades to make up for a sub-standard test score, and the red-flag scared everyone away.

He hoped to join childhood friend and St. Mary’s teammate Donald Coleman at the Hun School of Princeton, a preparatory school in New Jersey, but he didn’t academically qualify.

When things didn’t work out, Coleman encouraged him not to give up.

“I just told him get in anywhere, get the grades up, because I know when he gets on the field he can do it,” says Coleman, now a defensive back at North Carolina State.

The two still speak regularly, wishing each other luck before their respective games and occasionally reminiscing about little league football in Detroit, when Calvin's father would drive them to games in his soft-top green Cadillac.

From left, Dominique White, Michelle Wheeler, Blaine Ellington and Jaishon Ellington in 2007.

“He was disappointed (not to be playing football), but he knew our mother would want him to go to college,” Wheeler says.

Wheeler was afraid for her brother. She heard the whispers in the stands at his high school games. She didn’t want him to be looked at as just another black kid from Detroit, good for carrying a ball and nothing else.

“I know he loves football, but my main thing was, you got to get an education,” Wheeler says. “He was talking to me about walking on (the football team). I was like, ‘OK, that’s good. Can you please just make sure your grades are up?’”

White did exactly that and walked on the team the following summer, playing sparingly on special teams during the 2010 season.

“I always liked him, I thought he had ability, he just needed to get in shape,” Eastern Michigan coach Ron English said of White’s first year.

That first year on the team, Jaishon and Blaine were hanging out more and more at Dominique’s apartment.

It wasn’t a buddy-buddy thing with White. They still had to do homework, still had to do chores. They just responded better to him. Blaine and Jaishon say they don’t get away with anything with White looking after them.

“Being younger, he knows what we’re doing. Knows if we’re trying to be slick,” Jaishon says.

“He basically knows our next move,” Blaine says.

White felt obligated to step up, just as Wheeler had done for them years ago.

“I just thought, if I can get them in my hands, I could help them be successful,” White recalls. “I just want to help them excel.”

Wheeler was hesitant, but agreed it would be in the best interest of Blaine and Jaishon.

“They listen to Dominique," she says. "They really look up to him.”

But to have legal custody transferred, Jaishon and Blaine had to speak to Wayne County Probate Judge Freddie G. Burton, Jr.

“I basically told him that who I grew up with, that’s where I feel comfortable,” Jaishon recalls. Jaishon and Blaine had done this before, briefly living with an aunt before coming back to Michelle. The judge laid it out to them straight.

He didn’t want to see them again. Period.

Wheeler still drives the boys to school and helps White out, but it’s White and his longtime girlfriend, Jinay Patrick, 22, who at the parent-teacher conferences, cooking dinner every night, making sure homework is done and, for Jaishon, college application deadlines are met.

“I’m just so proud of Dominique and the boys, they’re doing so well,” Wheeler says

Patrick and White describe themselves as old souls, not caught up in what youthful transgressions they might be missing out on by shouldering the added responsibility.

Has Dominique ever given any thought to where the boys or he would be had he gone away for school? What if he wasn’t that consummate male influence in their lives, even when his own personal struggles mounted?

White contemplates the question, admitting he’d never even considered coming to Eastern out of high school. At the time, he wanted to get away from home.

After some deliberation, he quietly and confidently states, “God works in mysterious ways again.”

The grind

Up most days by 6:30 a.m., White gets Jaishon and Blaine off to school by 7 a.m., then he’s at the EMU football building by 8 a.m. for weightlifting, treatment (for the aches and pains of college football) or both, depending on the day.

With a full slate of classes, practice and team meetings, White usually isn’t home until after 6 p.m. Sometimes he’ll sneak home between class and meetings to prepare something for Jaishon and Blaine to eat when they get home, or to get a jump on dinner preparations.

When he gets home for the evening, it’s dinner, homework, maybe a little TV, then off to bed for all.

“It’s tough, it’s a lot. But I know God would want me to do it. I know my mom, my dad, would want me to do stuff like this,” White says. “I want to help them be young men, so they can help someone someday.”

Eastern’s running backs coach Doug Downing says White is exceeding his expectations on the field, but that he knew White had that type of ability. After meeting, Blaine and Jaishon, a father of two himself, Downing wasn't quite sure what to think.

“I can’t imagine that,” Downing says. “The biggest word is sacrifice. He’s making (a sacrifice) for the well-being of his brothers."

During an off week in the Eagles' schedule, the demands on White were lighter. But he didn’t use it to catch up on sleep. He drove to St. Mary’s with Dickerson and another teammate, Willie Williams -- whom White had let stay at his apartment last summer while Williams was between leases.

White visited Rychcik, got hugs from his favorite teachers in the hallway, went to chapel and eventually spoke with the team.

“I just talked to them about being a St. Mary’s man, keep their head straight and knowing their goals,” White says.

Dickerson shakes his head.

“I don’t know man, Domo ... he's different," Dickerson says. “Always looking to give back to somebody.”

But his duty is far from done, on and off the field. This is the beginning, English reminds. White struggled in the spring, and English surmises it may have been to the adjustment of handling his new responsibilities.

Nothing of the sort has arisen during the season.

“I think it’s a great story now, but it’s an even better story if he can maintain what he’s doing, both in school and football and finish it all with those kids,” English says. "The guy doesn't say two words. He keeps his mouth shut and plows ahead. ... Those are the kinds of guys you want on your team, because they're tough guys.

"We love having him on our team, I love what he's doing with those kids."

Pete Cunningham covers sports for AnnArbor.com. He can be reached at petercunningham@annarbor.com or by phone at 734-623-2561. Follow him on Twitter @petcunningham.

Comments

yourbiggestfan

Thu, Nov 24, 2011 : 10:32 p.m.

What a great guy. Isn't it amazing that the people with the busiest schedules always seem to find the time to do what is right. Kudos to Dominique!

steve h

Thu, Nov 24, 2011 : 6:36 p.m.

nice story. glad to see aa.com looking a little deeper.