FOIA Friday: On writing from public records

My morning links post Thursday on noise, chickens, block parties, dog licenses, and banners was written based on an analysis of the Ann Arbor City Clerk's published list of permits. It's convenient to write from published data, since the data you want has been gathered for you. Â

With any kind of analysis based on a single published source, there's always a few nagging questions as to whether you've told the complete story and whether the public record as published is comprehensive enough to rely on.

Here's another look at that set of reports, with a note to the questions that came up that might have been answered wrong or incompletely when based solely on the public record. Let it serve as a warning to the reader and to the author: it can seem easy to draw reasonable conclusions from a single data source, but you might not be getting the whole picture and thus, not the whole truth.Â

Noise permits

I wrote that the city had turned down two requests for noise permits in April on Greenwood Avenue. There was a third permit in March that had been turned down, for a Haiti benefit concert. One noise permit had been issued in January for the use of chainsaws on Main Street for ice carving.

What you can't tell from the public record, though, is how many people inquired about noise permits in the campus area but didn't apply because they'd been told that they would be denied. Thus there would be no "DENIED" in the public record because no permit had been applied for. If you cared to know further, it's either a matter of asking the people involved to describe their policy, walking up and down streets that would be likely to be affected and talking to residents, or going the slow and cumbersome Freedom of Information Act route to ask for records of email internal to the police department regarding the noise policies.

Tracking noise-related issues from a complaint perspective, rather than a permit perspective, is also a little bit harder than it might be writing solely from the published record. The police department's call for service log does not have a specific code assigned for noise violations, and thus those reports might be coded as one of several categories including "neighborhood trouble," "disturbing the peace," "disorderly conduct," or a catch-all "local ordinances."

You could track down all of the tickets actually issued, but that would not give you insight into the places where no ticket needed to be issued to quell the disturbance.

The calls-for-service log includes the date of each event, but it does not include a time stamp other than midnight. So it's not possible, for example, to pull out only the events that happen between midnight and 5 a.m. without further making a query to the city.

Block parties

The clerk's database of permits includes a single application for a block party, on Crest Street. The record, which stretches back six months in spreadsheet form, doesn't indicate any prior requests; the last one in the eTrakit system is from October 26, 2009, for a party on Donegal Court.

If you look back to last year, there were over 60 block parties applied for and only a handful turned down. One of these that was turned down was BLCK09-0037, a permit applied for a block party on Greenwood Avenue. The rejection letter notes:

"This is primarily a student housing area. We have not given these out to rental areas like this in the past. It is also student move in today and tomorrow, so I am going to deny this permit."

The database produced by the clerk has street addresses on many of the applications for permits, organized in such a way that some but not all of them are geo-coded already so that you can easily plot the locations of some permit applications on a map. Block parties are not entered with a location, however, so you can't readily take the data provided and plot the locations of each of the areas where permits were accepted or denied on a map without going through each paper application, one at a time, and entering that data.

If there's a "no student block party" zone, enforced by law or by custom, it will take effort and not a quick lazy blogger's cut and paste from public data to illustrate it.

Dog permits

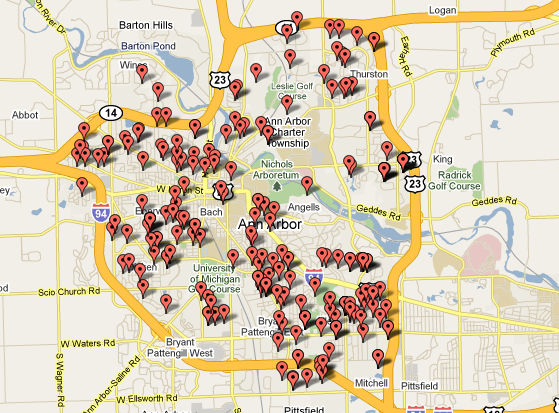

The map shows the addresses on file for the owners of the dogs who have received dog licenses from the City of Ann Arbor for the past six months.

Data from Ann Arbor City Clerk, mapped by Batch Geocode

One data set that is more carefully geocoded is dog permits. Most, but not all, of the dog licenses issued have a valid address in the spreadsheet, making it possible to create a map like this one to show where the dogs are.

If you look more closely at the data, some portions of it start to look a little bit less accurate, though not horribly so. Four addresses in this database correspond to locations which are outside the city limits of Ann Arbor; it's not clear if those reflect typographical errors, errors in the geocoding process, or any of a number of other plausible circumstances that would result in the case where someone who didn't live in the city bought a dog license for a dog that did live in the city.

The map is also misleading to the extent that it doesn't reflect dog licenses issued at the county level, especially to people who live in one of the many township islands that are within the city limits. It doesn't do anything to signal the presence of multiple dogs at a single location, and it only shows six months worth of licensing activity, meaning that dogs who got their license a year ago and who still have a valid dog license are not listed on the map.

There are 27 licenses in this database which do not show a zip code when the data file is imported into a spreadsheet. Those might reflect data entry errors and omissions, or there might be something else going on; it's hard to know for sure without more digging.

With a spreadsheet and some mostly clean data you get a pretty map. Is the map perfect? No. But you wouldn't expect a map like this to be perfect in an afternoon's work, and if there was some story about dog-friendly (or dog-hostile) neighborhoods that was driven by data analysis, this is a starting point, not an ending point.

Published data as a starting point, not an ending point

A look at noise permits, block party permits and dog licenses based solely on the information that anyone anywhere can download and analyze brings up as many questions as it answers.

None of the descriptions, maps, or narratives above could have been written if the sole access to this data was through the FOIA process. As I've written before, FOIA is the worst possible search engine, and it forces requests for information through a cumbersome and sometimes adversarial process that can drag out for weeks. By the time you found out about a block party via FOIA, the plastic cups would have been cleaned up off the streets.

The quality of the data received through this process is good, but it's not perfect, and to really understand it you have to go beyond the thing you're looking at and understand context. Not all of the CSV files that are published load neatly into Microsoft Excel, and if you are going to be perfectionist about it you'd want to go in and hand-check every single line to make sure that no stray commas came into to mess up the import.

Police call for service records are coded in such a way that even if you have a pretty good idea what you are looking for, the particular incident or event may have been recorded in one of one or more categories. Street addresses in police logs that are published by the city of Ann Arbor are deliberately obfuscated for privacy reasons, so that you might have a record specifying that an incident occured on 300 Main Street (not saying whether it's north or south) or the 1000 block of Washtenaw Avenue (which is a mile or so long).

I don't expect routine data dumps of non-critical transaction data to be 100 percent perfect. No one will be put out of their home if a clerk doesn't fill in all of the fields on a dog license form. The cleaner the data is, though, the easier it is to use it for routine insight into ordinary events, with time not spent hand-entering data available to use to understand what's going on.

You could file a "student parties are noisy" story every single spring and every single fall. There's a long history of alcohol-fueled interactions between students and the police, and a short email taken out of context doesn't tell the whole story.

FOIA requests in progress

Despite my recommendations to others to the contrary, I continue to file FOIA requests. Â I Â continue to get rejected in those requests, continue to appeal those rejections and continue to get interesting things back.

My request for a copy of the A2Fiber proposal was initially rejected. I appealed, and after an extension due to exceptional events, I received some but not all of the materials I requested. There's enough in there to dig through that I don't have a complete story to tell yet, but I do know that there's more in the response and the responses from other cities worth looking at.

I never sent in a FOIA request for the minutes of the Ann Arbor Historic District Commission. Instead, I walked over to City Hall and asked for them, and I was told that they didn't exist. A few disappointed looks and voicemail messages later, I was subsequently told that they did exist; you can see them on the Historic District Commission's meeting minutes archive.

Notable about this new set of minutes is that unlike previous editions of HDC minutes, which included long recitations of the Secretary of Interior's guidelines for windows or doors or historical preservation, these were prepared as "action minutes". Â Only the actions, in the form of votes by the members of the commission, were recorded. Presumably this is a way to document the relevant portions of the decision making process in a timely manner as specified by law in the Open Meetings Act. It means that if you wanted to hear the precise details of the discussion, you would have to turn to the video recording of the event and not rely on the text of minutes.

Edward Vielmetti has FOIA requests waiting for him at City Hall. You can reach him at 734-330-2465.