The myth of the self-made man

Tell me the place you were born

The lives that your ancestors led

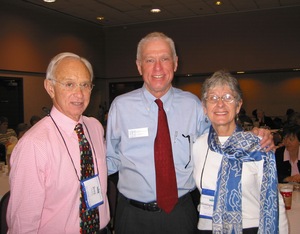

The ground that surrounded the people The “positive deviance” idea and the stories of Jerry Sternin, left, and Monique Sternin taught me about the problem-solving capacity that resides within communities, even when the problems seem intractable.

Dennis Sparks/Contributor

Our lives are fed by many streams. I am the eldest child of Clyde and Maryadele Sparks, a factory worker and waitress whose lives were shaped by the Great Depression and the Second World War. While their roots were blue collar, their aspirations for me included college and a white-collar workplace free from the insecurity and indignities of the world they knew.

There were other tributaries that fed the river of my life, though. Among those streams were teachers in the public school and university classrooms of the first decades of my life. In addition, there were a few special individuals whose ideas had a profound influence on me, although I initially only knew them through their articles and books. Three such individuals come immediately to mind, each of whom influenced me in unique ways: Carl Rogers, Jerry Sternin, and Parker Palmer.

Carl Rogers books and articles had a significant effect on me as a young teacher and graduate student. In Freedom to Learn, written in 1969, Rogers cautioned against prescribed curriculum, similar assignments for all students, lectures as a primary means of instruction, and the evaluation of learning through standardized tests. Rogers once observed, “The only person who is educated is the one who has learned how to learn and change,” a very different standard from those we use today to judge the quality of our schools.

I met Rogers when I was in my 30s after a lecture he gave in the late 1970s when he was approaching his 80s. He spoke, as I remember it, on the subject of “growing old, or older and growing.” We talked briefly, and I sensed a shy man whose vulnerability was one of his many strengths. Later I determined that I was most influenced by the books Rogers wrote after his 65th birthday, an awareness that in my 30s changed my sense of possibility regarding growth and contribution throughout one’s life span.

I first heard of Jerry Sternin in a Fast Company article that described his work with Save the Children in Vietnam. The idea that informed his life-saving efforts was incredibly simple—the know-how to solve pressing community problems more often than not already exists within communities rather than with outside experts. He used the term “positive deviants” to describe the people who possessed those solutions. I interviewed Jerry for a publication with which I was involved at the time. He told me, “People learn best when they discover things for themselves. Knowledge is usually insufficient to change behavior. . . . Positive deviance is very empowering approach, but it’s one that individuals with lots of degrees on their wall may find it difficult to implement. Positive deviance inquires in what’s working and how it can be build upon to solve very difficult problems. It requires that experts relinquish their power and believe that solutions already reside within the system.”

Later I met Jerry and his wife Monique and listened to their stories about seemingly intractable problems to which they had applied the positive deviance approach—malnutrition in Vietnam, the spread of HIV/AIDS among sex trade workers in the developing world, and genital mutilation of young girls in a country that would not allow public discussion of the problem yet alone exploration of solutions. Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard by Dan Heath and Chip Heath, published earlier this month, further explains this approach.

I came to know Parker Palmer through his books. The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life was the first I read in the late 1990s. “[R]eform will never be achieved,” he wrote, “by renewing appropriations, rewriting curricula, and

With Parker Palmer at a Fetzer Institute leadership retreat

What do I make of the lessons these teachers offered me, some of which in retrospect were “countercultural” in their influence? From my parents I learned the importance of aspiration and persistence in the face of adversity. From Carl Rogers I acquired a sense of possibility about learning, growth, and contribution throughout the lifespan. From Jerry Sternin I learned about the capacity of the community—whether that community is a neighborhood, school, or city—to solve its own problems given leaders who nurture that potential. And from Parker Palmer I learned that who we are on the inside matters and that our heart and soul have a place in our work settings as well as our homes and faith communities.

In considering their influence I am reminded that I am not a self-made man and, like everyone I know, a beneficiary of the people and institutions to whom I owe a profound debt of gratitude.

Dennis Sparks’ “Things Observed” photos and essays encourage readers to see familiar things in new ways. You can also read his blog on school leadership and contact him at dennis.sparks@comcast.net.

Comments

MIKE

Sun, Feb 28, 2010 : 11:18 a.m.

So true. I learned how influenced I was, and am, by those I've known in the past and those around me, while writing a memoir. Whole memoirs can be written around the influence of others in one's life, I found. It's good to understand what experiences really made the "self-made man," whether he/she is a success or failure. Good column. Mike