Landmark Fluxus exhibit at University of Michigan toys with the nature of art

“Exit” by George Brecht

Courtesy of the University of Michigan Museum of Art

If the works of art in the UMMA’s “Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life” seem unlike the art you know—and there’s certainly reason for much of it not to seem like art at all—then the work has done its job. Because the whole point of the art form (as well as the exhibit itself) is to question everything typically considered to be art.

In fact, the whole notion of a Fluxus aesthetic is what’s at stake in the exhibit. The artful children of 20th century French-American artist-provocateur Marcel Duchamp, the artists associated with Fluxus were and are (since the movement is still active) intent on questioning everything.

As UMMA Director Joseph Rosa explains in his brief introductory statement about the exhibit, “The Fluxus phenomenon helps us reexamine our perspectives on art objects and on the issues in our own lives.” Right—yet even this notion must be a bit qualified since the intent of Fluxus is ultimately to question the whole meaning of meaning.

The artform has many 20th century predecessors.

Among these influences are composer John Cage, whose 1950s experimental music explored indeterminacy in sound; poet Jackson Mac Low, who was exploring indeterminacy in word at the same time; Allan Kaprow, often credited as being the creator of the first art “happenings” of the late 1950s; and, of course, Duchamp himself, whose involvement with Dada and other sorts of conceptual arts led to many of this century’s most challenging artistic ideas.

Tying these diverse strands together was Lithuanian-American George Maciunas, who served the same function for Fluxus as Andre Breton for surrealism earlier in the 20th century. Maciunas organized the first Fluxus event in 1961 at the AG Gallery in New York City and the first Fluxus festivals in Europe in 1962. And like Breton, Maciunas culled the artists who joined his “movement”—often nurturing and excommunicating them at whim.

The artform quickly found adherents worldwide. As such, internationally famous Fluxus talents on display at the UMMA include George Brecht, John Cale, Nye Ffarrabas, Ken Friedman, Al Hansen, Milan Knizak, Alison Knowles, Shigeko Kubota, George Landow, Maciunas, Peter Moore, Claes Oldenburg, Yoko Ono, Nam June Paik, Dieter Roth, Takako Saito, Mieko Shiomi, Daniel Spoerri, Endre Tot, Ben Vautier, and La Monte Young.

Yet what is Fluxus?

The term is Latin; essentially meaning “to flow” (as in “to be in flux”). And does it ever live up to the title: Once assembled, this loosely knit group of artists, poets, musicians, architects, composers, and designers, set about reinventing art, even if it meant burning it down.

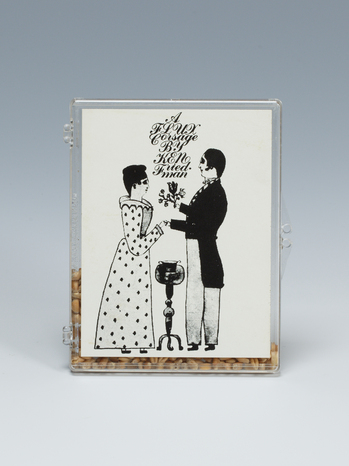

“A Flux Corsage” by Ken Friedman

Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, George Maciunas Memorial Collection: Gift of the Friedman Family.

There’s a concentrated emphasis on personality (through both political acts and personal opinions) rather than a focus on traditional mediums in Fluxus. Through the 1960s and 1970s, during its heyday, Fluxus staged live events (often in the form of art installations) that featured unconventional materials—from “fluxkits” of found objects to musical “event scores”—supplementing installation sculpture, video, and performance art.

On the other hand, Fluxus has definite aims, described in the gallery statement as a cosmic “interpretation and response” to art through “design and layout.”

As the UMMA’s statement tells us, “The exhibition playfully supplies answers to fourteen themes framed as questions, such as ‘What Am I?,’ ‘Happiness?,’ ‘Health?,’ ‘Freedom?,’ and ‘Danger?’”

With other heavyweight topics including the metaphysical concept of nothingness and the perennial issues of life, love, sex, and death, no one can accuse Fluxus of shrinking from the big existential questions—even if the answers themselves are a bit eccentric. Despite a sometimes cynical veneer, these works attempt to coerce viewers to consider the most abstract issues.

Take two art cinema examples: Nam June Piak’s 1964 “Zen for Film” and Yoko Ono’s 1966 “Fluxfilm No. 14: One.” Neither film follows traditional cinema with regard to structure, but both films push the boundary of our understanding of cinema itself.

Ono’s “Fluxfilm No. 14: One” (filmed by Peter Moore) is only a few minutes long, shot with a high speed camera at 2000 frames per second. It features an ultra-slow close-up of a match being struck in front of the camera. It’s hypnotic in its offbeat manner; off-putting in part, but also absorbing.

Piak’s “Zen for Film” is filmmaking at its purest. Paik has set up a clear 8mm leader loop running through a projector that casts a perpetual blank image against the UMMA wall. At most, waiting for particular scratches to rotate through this projected loop keeps one’s attention active.

Of his many contributions, Maciunas’ 1970 “Multifaceted Mirror” is an excellent artwork by any standard. His “Mirror” is created out of 49 half-inch plates of polished metal braced by plastic in a wooden case. Balancing smartly on this convex surface, his concave collection of plates creates a multitude of reflections that shift with the viewer’s movement by playing on the notion of multiple representations as opposed to our integrated sense of self.

Among other artworks, Milan Knizak’s 1972 “Killed Book” says volumes about politics with its hardback, red flagged book riddled with bullet holes. Endre Tot’s “Dear Stanley … I am Glad I can Type Zeros” uses a mailed postcard that has row upon row of typed zeros running across its surface to make its decimal point. And Daniel Spoerri’s 1965 monotone screen-print “Meal Variation No. 2, Eaten by Marcel Duchamp” from his “31 Variations on a Meal” is, like Fluxus itself, simultaneously historic and ephemeral.

Much the same thing can be said of the hundreds of other historic yet ephemeral art objects in “Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life.” Each artwork strives to mean something even as it wants to tell us that it doesn’t mean anything.

By taking art to its logical end, these artists have returned from where they began. And this makes the UMMA’s “Fluxus” a supremely heroic aesthetic—even despite itself.

“Fluxus and the Essential Questions of Life” will continue through May 20 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. Museum hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday, and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.

Comments

Dog Guy

Wed, Mar 7, 2012 : 2:34 p.m.

It's that time on the month? I must visit UMMA.