UMMA exhibit showcases 'Out of the Ordinary' pieces of folk art

"Stone Eater" by Alain Mailland

courtesy of the University of Michigan Museum of Art

"Out of the Ordinary: Selections from the Bohlen Wood Art and Fusfeld Folk Art Collections" at the University of Michigan Museum of Art certainly lives up to its title.

The exhibit, on display in the UMMA’s spacious A. Alfred Taubman Gallery II, is art that’s as sincere as it can get. A two-part exhibit organized by Kristine Ronan, doctoral candidate in U-M’s Department of the History of Art, the display consists of two aesthetics well off the routine artistic path.

The Robert M. and Lillian Montalto Bohlen Collection of Wood Art is not your run-of-the-mill wood art. The works in this half of “Out of the Ordinary” represent differing approaches 20th century wood-based sculptors have made to a time-honored functional craft.

In some instances, the woodworker has adapted lathe turning until the technique takes on equal importance to the finished object.

“As lathes disappeared from factories,” says Ronan in her gallery statement, “they were adopted in high school classrooms as standard tools for the manual training of future industrial workers. By the 1920s, such training was at an all-time high in the United States. In the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, a first-generation of innovators—now considered the ‘fathers’ of contemporary woodturning—expanded on the usable vessels that they had been trained to make in these 1920s industrial arts classrooms.”

The Bohlen Collection half of “Out of the Ordinary” thus illustrates the remarkable range of nontraditional contemporary wood art during this evolution, where the relentless bending of woodcarving tools now suits the sculptor’s imagination as much as it suits the medium’s form.

For example, Gianfranco Angelino’s 1994 “Ribbed Birch Plywood, Sumac Plate” illustrates the subtle tension this late Italian sculptor brought to his functional art. Through his nontraditional use of traditional materials in a traditional plate design, Angelino’s “Ribbed Plate” is composed of birch plywood, sumac branch, and ebony pins where strips of these materials construct a cross-hatched plate. The result is a traditional function that reflects the novel applications 20th century wood sculptors brought to their work.

Mark Lindquist’s 1994-95 oak burl “Double Totemic Sculpture” features what Ronan describes as “sculptural sensibilities (married) with new turning techniques.” In this instance, Lindquist has chain sawed a cylindrical tube out of stacked wood trunks that widens at both top and bottom with a tapered torso at center. The work is as muscular as is the approach to it.

"Spirit Dancer" by Mark Bressler

courtesy of the University of Michigan Museum of Art

Arguably the masterwork of the Bohlen display is Santa Fe sculptor Mark Bressler’s “Spirit Dancer.” This magnificent 2002 madrone burl free-standing sculpture uses many of the artistic innovations of 20th century woodworking in conjunction with a particularly dramatic trunk to create a four-foot artwork whose jagged opening suggests motion as much it does permanence. Bressler’s dramatic and superbly tactile “Spirit Dancer” energetically explodes from its being.

By contrast, the Daniel and Harriet Fusfeld Folk Art Collection is about as old school art as “no school” art can get. The art of this collection reflects “outsider” art—that is, art of an untrained vision—that’s only now being recognized as having equal footing with what is sometimes called “high art.” While that art was making the history books, folk art was busily recording an unvarnished view of our country’s heritage.

Ronan writes, “Much early folk art is the expression of earlier artistic practices carried to the New World by European immigrants and African slaves.

“Folk artists varied greatly in their professional background and training. Some artists were self-taught men and women who created elaborate objects for decorative or functional use in their homes. Other artists were boys and girls schooled in academies, who created folk art as demonstrations of their refinement and skill. Still other folk artists were professional artistic practitioners of their day, traveling from village to village as itinerant painters.

“And despite how we think of folk artists as ‘ordinary’ Americans, many folk artists attained professional training through apprenticeships or studies available through prints or at local museums.”

"Portrait of a Woman"

courtesy UMMA

The 28 artworks drawn from the Fusfeld Folk Art Collection in “Out of the Ordinary” follow this modest inspiration with examples of folk arts ranging from 19th century professional studios to the sort of art produced by personal incentive with little to no attempt to craft within received tradition.

As a result, this work has a visceral authenticity, because these artists’ lack of guile is accompanied by an urgency of unique personal vision. Essentially, these artists are storytellers who used whatever media were within their reach and whatever talent they possessed, so there’s little to no artifice to interfere with their insight.

Illustrating the exceedingly fine border in 19th century art between folk art portraiture and high art portraiture, the New England-based Prior-Hamlin School’s circa 1840 “Portrait of a Woman” touches both sides of America’s artistic divide of that time. Too polished a painting to be naïve, the portrait also bears a simplicity of design that was apparently underestimated as fine portraiture of that era. Yet there are details in the work—for example, the discreet complexion of the model’s cheeks and the close attention to her eyes—that clearly mark the painting as the effort of a professional portraitist rather than an amateur painter.

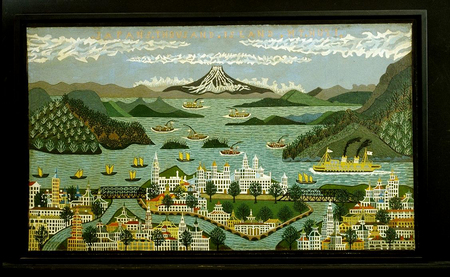

"Japan’s Thousand Island Mt. Huzi" by Karol Kozlowski

courtesy of the University of Michigan Museum of Art

On the other hand, New York City-based, Polish immigrant Karol Kozlowski’s 1960-65 oil on canvas “Japan’s Thousand Island Mt. Huzi” is an example of a naïve artist whose hobby ultimately defined his creativity. Ronan notes that Kozlowski only completed 36 paintings in his lifetime due to his daily work routine and cramped living quarters. Yet there’s a striving for excellence in this remarkable landscape painting that mingles a tightly rendered geometric abstraction cityscape with elongated horizontal brushstrokes of the volcano’s waterline to suggest a personalized neo-Impressionism. Kozlowski clearly was not uninformed in art history; rather, he absorbed what he chose and crafted his work accordingly.

Closer to a naïve, yet also street-savvy 20th century abstraction, is Purvis Young’s 1997 “Three Guitar Players.” This vigorous paint on composition board artwork is a passionate figurative abstract expressionism. There’s just enough detail in the painting to suggest a hearty rhythm and musical motion; because, ultimately, Young is depicting his urban milieu as much as he’s providing an off-the-cuff portrait of music and musicianship. His “Three Guitar Players” is an unusually cagey and concise narrative.

“Out of the Ordinary: Selections from the Bohlen Wood Art and Fusfeld Folk Art Collections” will continue through June 26 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. Museum hours are 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday; and noon-5 p.m. Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.