UMMA showcasing big-hearted work of 'Sister Corita'

Corita Kent’s work is an example of 20th century pop art meeting flower power’s peace, love, and understanding. But there’s a joyful wisdom to this artist’s oeuvre — that makes the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s “Sister Corita: The Joyous Revolutionary” — a doubly fascinating exhibit.

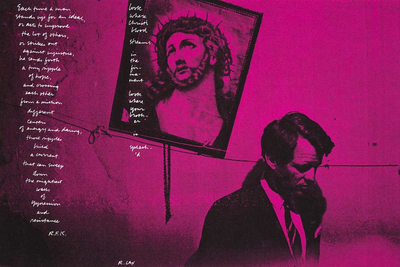

"in memory of rfk" silkscreen print on paper by Sister Corita Kent, on view in "The Joyous Revolutionary" at UMMA.

Born Frances Elizabeth Kent in Fort Dodge, Iowa on November 20, 1918, the artist moved with her family to Los Angeles as a child, where she was educated in parochial schools. Kent joined the Order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1936 at age 18, taking the name Sister Mary Corita (a Greek variant of Cora, meaning “idealistic”). And after teaching elementary school in Canada for four years, Corita returned to L.A. to teach art in the art department of Immaculate Heart College.

In 1951, she received a master’s degree in art history from the University of Southern California. During her last semester there, Corita took a serigraphy class, producing her first limited-edition silkscreen prints. The next year, she entered one of her artworks in the Los Angeles County Museum exhibition, winning first prize for printmaking. That print, “the lord is with thee” also won first prize at the California State Fair.

This recognition launched Kent's career as an artist. But among her other talents were administration and editing; where she crafted a periodical, “Irregular Bulletin,” that was noted for the range of its contributors.

From the 1950s through the late 1960s, Corita was the departmental chair of what industrial design author Ralph Caplan called the “hippest college in Christendom”—the increasingly famous Immaculate Heart College Art Department. But internal discord led Corita to leave the order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in 1967.

She moved to Boston and adopted the name of Corita Kent. And in Boston’s Back Bay, Corita made numerous commissioned works, continuing to create serigraph prints through the next 18 years. She was diagnosed with cancer in 1977; succumbing to the illness nine years later.

What a life — and what remarkable art.

As the UMMA’s gallery statement states, the exhibit, comprising 44 prints (and three photographs) “illustrate Sister Corita’s signature work beginning in the 1960s, which broke free from the more traditionally religious or Biblical imagery to works that encompassed a wider concept of spirituality.

“Inspired by media and advertising,” continues the statement, “she began her evocative use, reuse, and re-contextualization of everyday phrases and images to create art that addressed contemporary issues ranging from poverty, materiality, and environmental degradation to inequality, social injustice, and war.”

Leading us back to the notion of flower power meeting pop art — because this is precisely what one finds of Corita’s work. Her earliest works (for example, 1957’s silkscreen print on paper, “custodiat”) features 1950s post-painterly abstraction meeting Art Brut with its burgundy color-field background set against an abstracted airplane that’s been inchoately flattened with a mid-ground blue color-field holding the plane securely in its palm. The work’s title — Latin meaning “to guard” — finds Corita mingling these visual cues with the work’s title printed aside the initials of the young boy, William Daly, for whom the work was executed.

Interestingly enough, Corita's 1950s prints in this display feature decidedly dark palettes. Their sheer density gives indication that she was working through some heavy concepts at the time. The inventiveness of her imagery lends itself to contemplation. And given their overt religiosity (“at cana of galilee,” “christ and mary,” and the before mentioned “custodiat”), Corita was working from within the constraints of her avocation.

By the early 1960s the artful cuffs start to come off. Corita’s choice of color lightens and 1963’s silkscreen on paper “hi” illustrates a transition toward a full-fledged pop sensibility emerging with a corresponding reduction of her palette. Where the word “custodiat” was scrawled across the print by that name; “hi,” by contrast, is cleverly abstracted within the print’s blue and red colorfield through a playful gestalt.

By the mid-1960s Corita found her stride. And 1966’s silkscreen on Pellon “apples are basic” surrenders to art for art’s sake, albeit with a nod to her religious beliefs. Corita nearly celebrates the possibility of redemption through understanding. The green words “big time” brace the words of the title with abstracted print-laden red apples in the print’s right corner. Still, the work’s ambiance (like all pop art) has a cheerful, almost subversive quality.

It’s all the more shattering, therefore, that the signal print of the exhibit is 1968’s silkscreen on paper “in memory of rfk.” This crimson-tinged masterpiece — somberly following Andy Warhol’s use of photographic imagery transferred to the screen — catches the slain presidential candidate with his gaze cast wearily down as he passes a framed portrait of a supplicating Christ. In this magnificent artwork, using her talent as a printmaker with her social and religious sensibilities intact, Corita crafts a profound sadness through expert photojournalism and contemplative art.

"yes number 3" silkscreen print on paper by Sister Corita Kent, on view in "The Joyous Revolutionary" at UMMA.

It’s therefore gratifying to see 1979’s jubilant “yes number three.” This famed silkscreen print is as concise as any artwork could ever be and as big-hearted as any artwork could ever aspire. Corita is subtly melding her philosophy of life to a concise pop art sensibility.

“Yes number three” is an ecstatically mature aesthetic with wholehearted attitude. It illustrates soulfulness by common example and reflects an unyielding optimism that’s equally unbreakable. Corita passes along this simple yet also acutely complex message to her viewer in a direct, unmediated way that’s meant to be forever inspiring — and it is.

“Sister Corita: The Joyous Revolutionary” continues through August 15 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 South State Street. Museum hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday-Saturday; and noon to 5 p.m., Sunday. For information, call 734-763-UMMA.

John Carlos Cantú is a free-lance writer who reviews art for AnnArbor.com.