University of Michigan Library exhibit details history of the Bible

"A History of the Bible" will remain at the Hatcher Graduate Library through March 7.

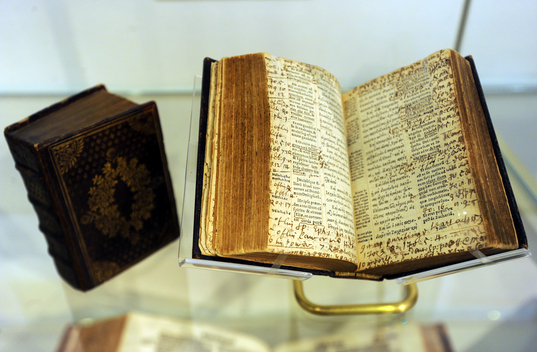

Lon Horwedel | AnnArbor.com

The University of Michigan Library system holds the most extensive collection of papyri in the western world. A sampling of those holdings forms the basis of a new exhibit at the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library: "A History of the Bible from Ancient Papyri to King James."

Every item in the exhibit comes from the university's Papyrus Collection and its Special Collections Library.

"A History of the Bible" begins with ultra-rare Egyptian papyri retrieved by University of Michigan researchers in the 1920s and 1930s, including Professor Francis W. Kelsey, who took the inaugural trip to Egypt in 1920. Kelsey returned from Egypt with 617 papyri.

Today, the university's Papyrus Collection has more than 7,200 documents.

The exhibit opens with a census declaration, written in 119 C.E. The declaration "reflects the practice of taking census in the Roman Empire and...documents a practice described in the Gospel of Luke," the exhibit explains. Censuses were taken every 14 years in the Roman Empire; the declaration displayed comes from 118 C.E., documenting the occupation and family members of an Egyptian man named Horos.

Another piece, an excerpt of the only known Greek text of the last chapters of the Book of Enoch, highlights the rarity of the pieces in the Papyrus Collection. Only six leaves from the Greek codex survived; two are at the University of Michigan, the remaining four are at the Chester Beatty Collection in Dublin, Ireland.

In the western Christian tradition the Book of Enoch only appears in bibles containing the Apocrypha.

Some of the university's better-known papyrus holdings come from the Epistles of Paul. P46, as the codex is known, is the earliest known copy of the Epistles of Paul. Of the existing 86 leaves from that text, 30 reside in the Papyrus Collection.

As brittle papyrus gave way to sturdier parchment which gave way to paper, which we still use today, two major advances remained: the use of a printing press and translation of the Bible out of Greek and Hebrew into "vernacular languages," like English.

We know Johann Gutenberg as the inventor of the printing press. But according to "A History of the Bible" that invention put Gutenberg deep in debt. In 1449, a merchant, Johann Fust, loaned Gutenberg the money to print a large-sized Bible. But as the exhibit explained, by 1456 Gutenberg was forced to relinquish his claim to the printing press to Fust.

Of the 200 copies of the "Gutenberg Bible" that were originally printed, 45 still exist.

Other Bibles on display reflect the politics of translation. William Tyndale's reward for printing the first translation of the New Testament in English in the mid-1520s was death at the stake in 1536. Some of Tyndale's translation has survived - the phrase "salt of the earth" being one - and Tyndale is credited with a heavy influence on the King James Version. But Tyndale paid the ultimate price for being ahead of the curve.

The "Great Bible," known in some circles as the Coverdale Bible, published in 1539, was the first English translation authorized for public use. Because Coverdale was well-liked by England's then-prime minister Thomas Cromwell, he kept his life and saw seven editions printed in a two-year period.

The exhibit closes with one of the most common texts on the planet, the King James Bible, which at the time of its printing in 1611 was considered the best English translation in existence.

King James I of England commissioned the Bible in 1604, hiring 47 scholars to translate the work into English while keeping the text "as consonant as can be to the original Hebrew and Greek."

Six groups of scholars, two groups each at Westminster, Oxford and Cambridge, tackled the job. Each group translated an assigned portion of the text. Once those translations were received, a group of 12 scholars reviewed them for accuracy. After the approval of bishops and the privy council, James himself gave his blessing in 1611.

"(That) the King James Bible succeeded where other translations had not," the exhibit explains "may be due to the fact that the text is (the work) ... of a large number of scholars working cooperatively and with ample time for thorough revision."

Previous English translations of the Bible fell out of favor due to the politics of the time or the politics of the translator. With the investment from a British king and the blessing of the powers that be in religious communities across the English-speaking world, the King James Version became the new gold standard and remained that way for more than three centuries.

"A History of the Bible" will remain at the Harlan Hatcher Graduate Library's Aububon Room through March 7.

James David Dickson can be reached at JamesDickson@AnnArbor.com.

Comments

Stefan Szumko

Fri, Feb 12, 2010 : 12:05 a.m.

When will these texts become a part of the Google Books project?

Freemind42

Thu, Jan 28, 2010 : 9:16 a.m.

But I thought that the Bible was the direct word of God? I guess even supreme dieties outsource manual labor.