Movie telling story of 'The Girl in Centerfield' premieres in Ypsilanti Saturday

• Related story: Long after she helped changed Little League, Carolyn King's legacy remains alive and well

Although 1973 was a pretty memorable summer for Ypsilanti’s Carolyn King — who, at age 12, made national headlines for being a girl who wanted to play what was then boys-only Little League Baseball — the story has largely been lost to time.

Howell writer Buddy Moorehouse and Grosse Pointe filmmaker Brian Kruger aim to change all that by way of a documentary film called “The Girl in Centerfield,” which is having its public premiere at Ypsilanti High School on August 21 at 8 p.m. as part of the Ypsilanti Heritage Festival.

Check out the movie's 10-minute trailer:

“I was on the team with Carolyn in 1973, so I was there at the beginning,” said Moorehouse. “It was just … this fascinating thing to go through, to see the attention that it got. … Brian and I started talking about (making a film about it) last year, so we looked around at what was out there on the subject, and there wasn’t much.”

PREVIEW

- What: Locally-made documentary about Carolyn King, who, as a 12 year old in Ypsilanti in 1973, unintentionally stirred a national controversy when she tried out, and made, a local Little League Baseball team.

- Where: Ypsilanti High School, 2095 Packard Road.

- When: Saturday, August 21 at 8 p.m. (during Ypsilanti’s Heritage Festival).

- How much: Tickets are $10, available at the door.

This, despite the fact that the controversy stirred a heated national debate and became a legal showdown between the City of Ypsilanti (the City Council voted unanimously to deny the League use of local fields unless King played) and Little League's national organization, which threatened to remove the city’s Little League charter.

“What that meant was you were not a Little League-affiliated league anymore, so there would be no east-west all-star game, and the teams couldn’t compete for the Little League World Series,” said Moorehouse. “We’d lose our insurance, and have to get other insurance, and there was equipment that belonged to (the League) that we wouldn’t be able use anymore.”

According to Moorehouse, the most painful loss on that list involved the annual all-star game, which pits the National League All-Stars from Ypsilanti’s east side against the American League All-Stars from the city’s west side. (As part of this weekend's events, that game will finally be played.)

Of course, King had had no idea what lay in store when she attended Little League tryouts with one of her brothers in the summer of 1973.

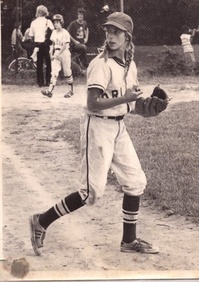

Carolyn King in 1973.

“I was just a tomboy, and at that time, there were no organized leagues at all for girls to play in,” said King. “No soccer, no softball — there was nothing for us to do in the summertime. We lived across the street from a park, and most of the neighborhood boys wanted to play basketball or tennis or baseball, so I’d just play with my brothers.”

On the night of her Little League tryout, King got a phone call from someone telling her she’d been drafted by the Orioles. She started attending practices, and the first people she had to win over were her teammates — which she did.

“It wasn’t that way at first,” said Moorehouse. “When we first heard about it, we were like, ‘Man, the team isn’t that good anyway, and now there’s going to be a girl on it?' But Carolyn was so nice and so unassuming — not obnoxious or annoying at all — that after a couple of practices, we came to accept her.”

More than that, the team stood by King as the media frenzy around the story grew, and as King’s opponents attacked her.

King described how she struggled to get to an Orioles game because her street was so clogged with media trucks and vans; and once she arrived, the field was packed not only with spectators who were there to boo her triumphs and cheer her failures, but also more members of the media.

Carolyn King in "The Girl in Centerfield."

Editorials about King appeared in newspapers all over the country; evening news anchors, including Walter Cronkite, covered the story; some of King’s opponents suggested that the National Organization for Women or Ms. Magazine had hatched the whole thing in order to press the issue; and while King received some wonderful, encouraging letters of support, she also got dolls (indicating she should be playing with them instead of baseballs) and nasty letters in the mail — which her parents began to intercept in order to shield her.

Additionally, the players on other teams resented King for putting their season in jeopardy. And indeed, Little League Baseball soon revoked Ypsilanti’s charter, as it had threatened to do. (The League had a rule that specifically said that only boys could play, supported in part by an American Medical Association report that pronounced that girls shouldn’t play contact sports like baseball.) The city sued the League, charging that it was illegal for them to revoke the charter when it appeared that King was qualified to play.

And while Ypsilanti ultimately lost in court, Little League Baseball invited girls to play the following year, in 1974. Now, more than 5 million girls play each summer. This evolution first sank in for King when she threw the first pitch at Ypsilanti’s Little League opener last year.

“I got a lump in my throat, and somehow, it just kicked in,” King said. “One of the coaches there said, ‘All these little girls are out here because you went out and played first.’”

King at last year's opening day:

But as “The Girl in Centerfield” makes plain, Ypsilanti officials deserve much credit, too.

“It was heroic what they did,” said Moorehouse. “There’d been plenty of other girls who had tried to play Little League, and who had gone to tryouts. A girl in New Jersey played three games, and then Little League Baseball said ‘You need to kick her off,” and they did. But Ypsilanti stuck up for Carolyn. … If not for that, her story would be like all the others.”

“I was raised in a community of great people,” said King, who now works as an assistant to a retired NFL player. “I’m just so very proud to live there, and I’ve lived there all my life.”

Kruger and Moorehouse are shopping “Girl” around to ESPN (which is working to launch ESPNW for women's sports), Lifetime and Discovery Channels, which have all expressed interest; in addition, they will submit “Girl” to film festivals this winter.

But what were the challenges of making the film?

“Before ‘87, unless parents had super 8 movie cameras and took them to the games, there’s nothing there, footage-wise,” said Kruger. “ We scraped together archival footage, but … there’s not that many photos, either. We had to scrap around town for visual images.”

Kruger, who’d also grown up in Ypsilanti, had run into King last summer, and this chance meeting was part of what planted the seed for the film.

“It just brought it all back,” Kruger said. “We did our first interviews, and when you listen these coaches talking about it — even though the story had slipped from your mind for a while, you realize all over again how significant, how huge it was.”

Jenn McKee is the entertainment digital journalist for AnnArbor.com. Reach her at jennmckee@annarbor.com or 734-623-2546, and follow her on Twitter @jennmckee.

Comments

Snarf Oscar Boondoggle

Sat, Aug 21, 2010 : 1:49 a.m.

very cool. there -is- someting about kids who know what;s decent, inherently. i wish there were two days of screenings, sat&sun, 'cause on sat i;ll be at the tigers game. sigh...oh,well.